China

China

Last updated: February 2024

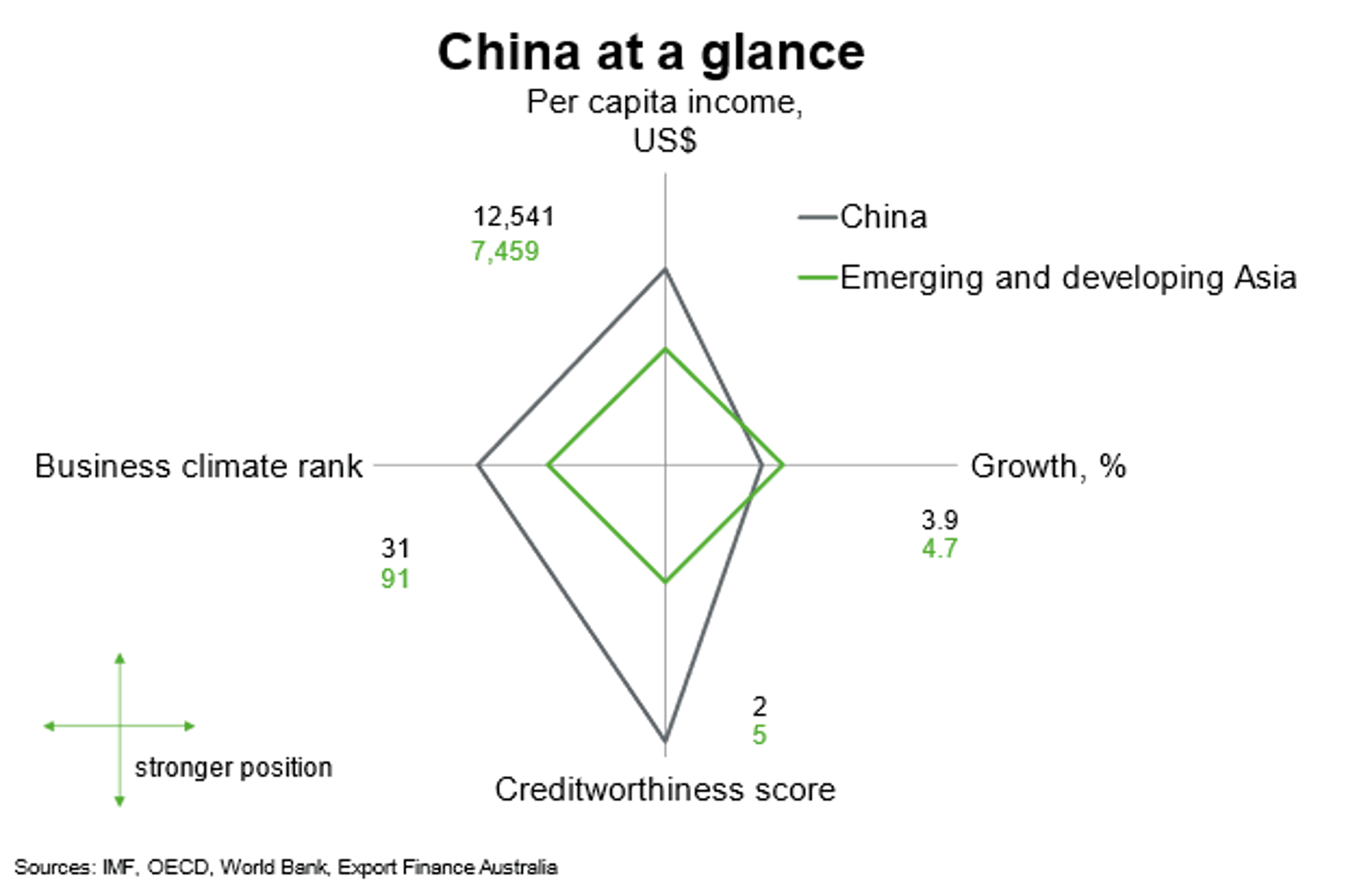

China is the world’s 2nd largest economy, behind the US, and outperforms its peers in emerging and developing Asia on indicators of per capita income, creditworthiness and business climate. The growth outlook lags that of the rest of the region.

This chart is a cobweb diagram showing how a country measures up on four important dimensions of economic performance—per capita income, annual GDP growth, business climate and creditworthiness. Per capita income is in current US dollars. Annual GDP growth is the five-year average forecast between 2024 and 2028. Business climate is measured by the World Bank’s 2019 Ease of Doing Business ranking of 190 countries. Creditworthiness attempts to measure a country's ability to honour its external debt obligations and is measured by its OECD country credit risk rating. The chart shows not only how a country performs on the four dimensions, but how it measures up against other regional countries.

Economic outlook

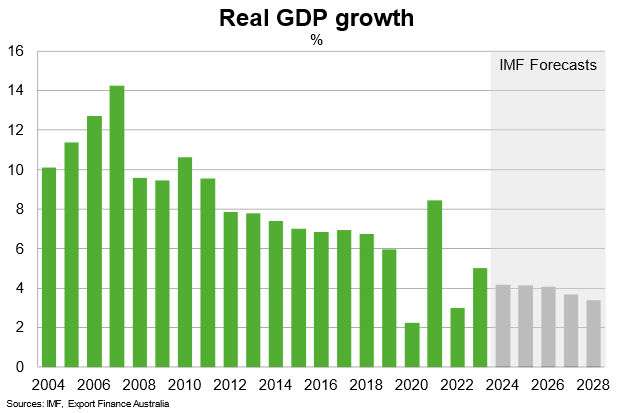

The Chinese economy emerged from pandemic restrictions in 2023, helping economic growth recover to 5.2%, from 3% in 2022. Growth momentum slowed towards the end of the year; reflecting slower retail sales growth and continued declines in property investment. Labour market conditions have remained weak (including subdued wage growth and high youth unemployment). The property sector continues to face challenges stemming from slumping sales and financial difficulties amongst developers. The ongoing plunge in the stock market is a drag on consumer confidence. The authorities have implemented several stimulus measures, including cuts in interest rates, lower bank reserve ratios and stronger infrastructure spending, though they have provided only a limited boost to sentiment and growth.

The IMF expects growth to slow to 4.6% in 2024 on the back of the ongoing property sector downturn. Public investment, however, will remain robust. The IMF expects exports to recover modestly on the back of improving electronics demand.

Risks are tilted to the downside. A further increase in energy prices and faster than expected tightening in global financial conditions would weigh on growth. Longer term, rising geopolitical tensions, particularly between the US and China, pose risks to external trade. High debt among corporates, banks and state-owned enterprises raises the risk of financial shocks.

Growth will be slower in the coming decade than it has been in the past, with the IMF forecasting growth to average 3.8% between 2025 and 2028. This reflects a shrinking population, slower productivity growth, and falling returns from investment. China’s economy will also face the difficult task of rebalancing to achieve sustained growth over time. This includes the shift from external demand to domestic demand and from investment and industry-led growth to greater reliance on consumption and services; a greater role for markets and the private sector in driving innovation and the allocation of capital and talent; and transitioning from a high to a low-carbon economy. Underlying drivers of growth still include China’s manufacturing dominance, while investment in advanced manufacturing should improve long-term growth prospects.

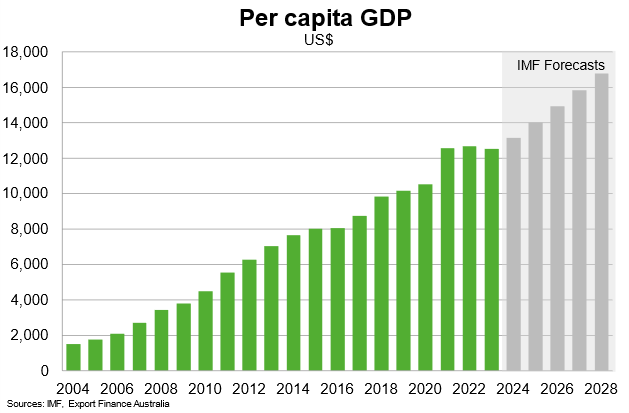

Alongside continued economic growth, per capita income will increase towards US$16,800 in 2028 according to IMF projections, up from around US$12,500 in 2023. The growing push into knowledge-intensive industries should pave the way for a rise in incomes over the longer term.

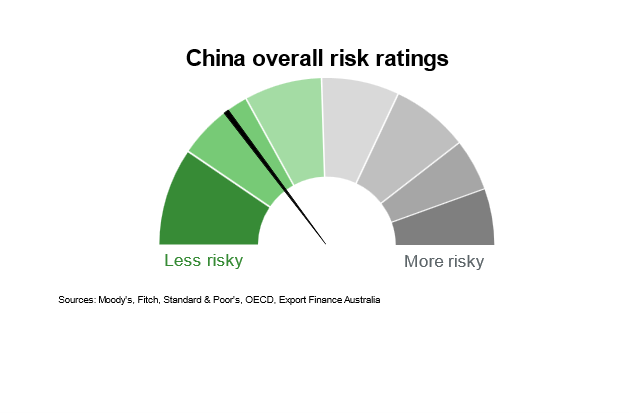

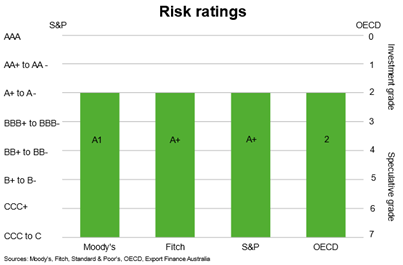

Country risk

Country risk in China is low. China has an investment grade sovereign credit rating from private ratings agencies and an OECD country credit grade of 2. This indicates a relatively low likelihood that it will be unable or unwilling to meet its external debt obligations. The elevated economy-wide debt burden, particularly among state-owned enterprises and corporates, remains a risk to China’s country ratings.

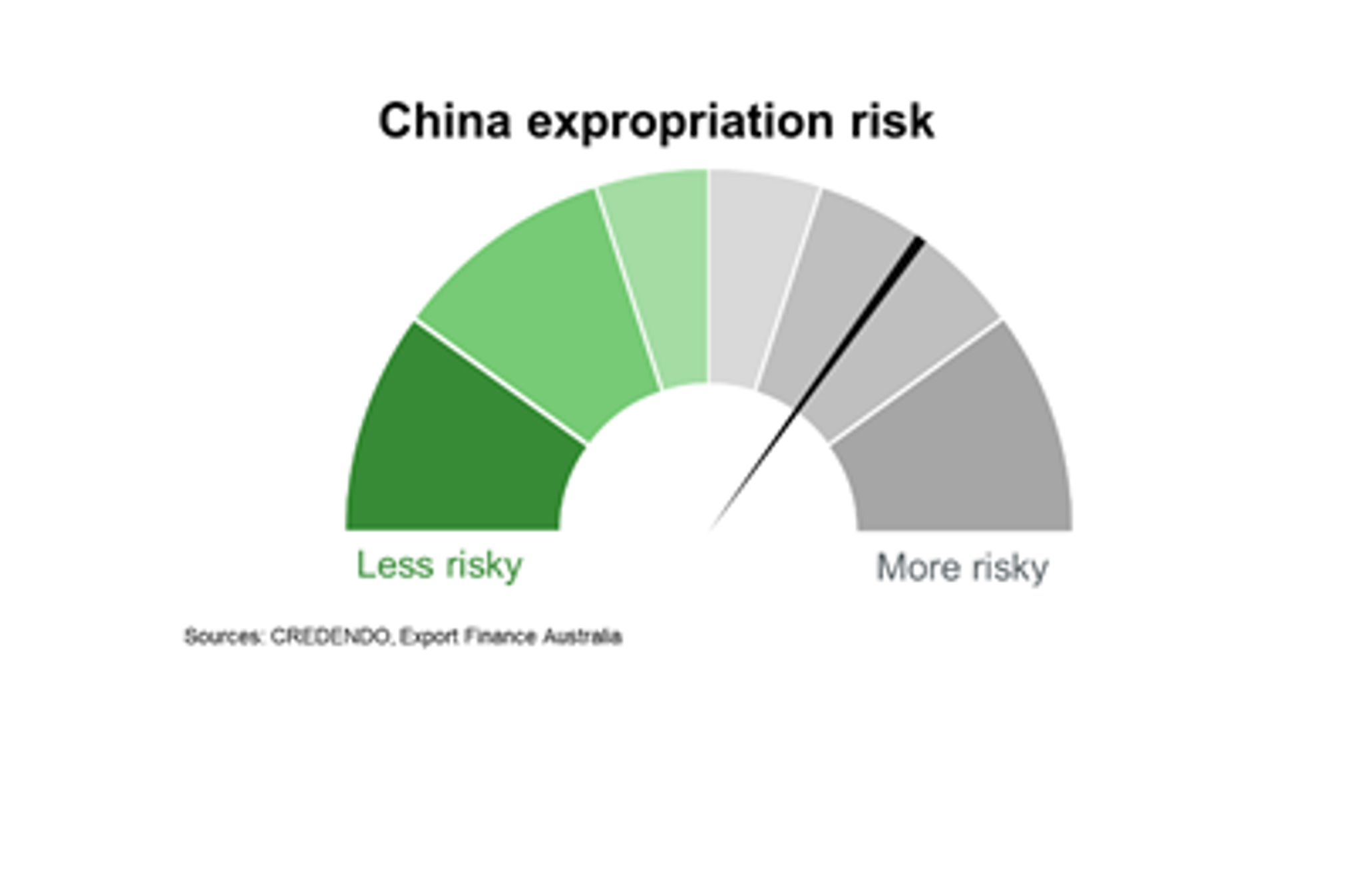

The risk of expropriation is elevated relative to China’s overall rating. According to the US investment climate statements, Chinese law prohibits expropriation of foreign invested firms, except under “special circumstances” where there is a national security or public interest need. Chinese law requires fair compensation for an expropriated foreign investment, but does not detail the method used to calculate the value of the foreign investment. Further, China’s many bilateral and multilateral free trade agreements, in general, cover topics like expropriation and investment arbitration mechanisms. The US is not aware of any cases of expropriation of US investments since 1979.

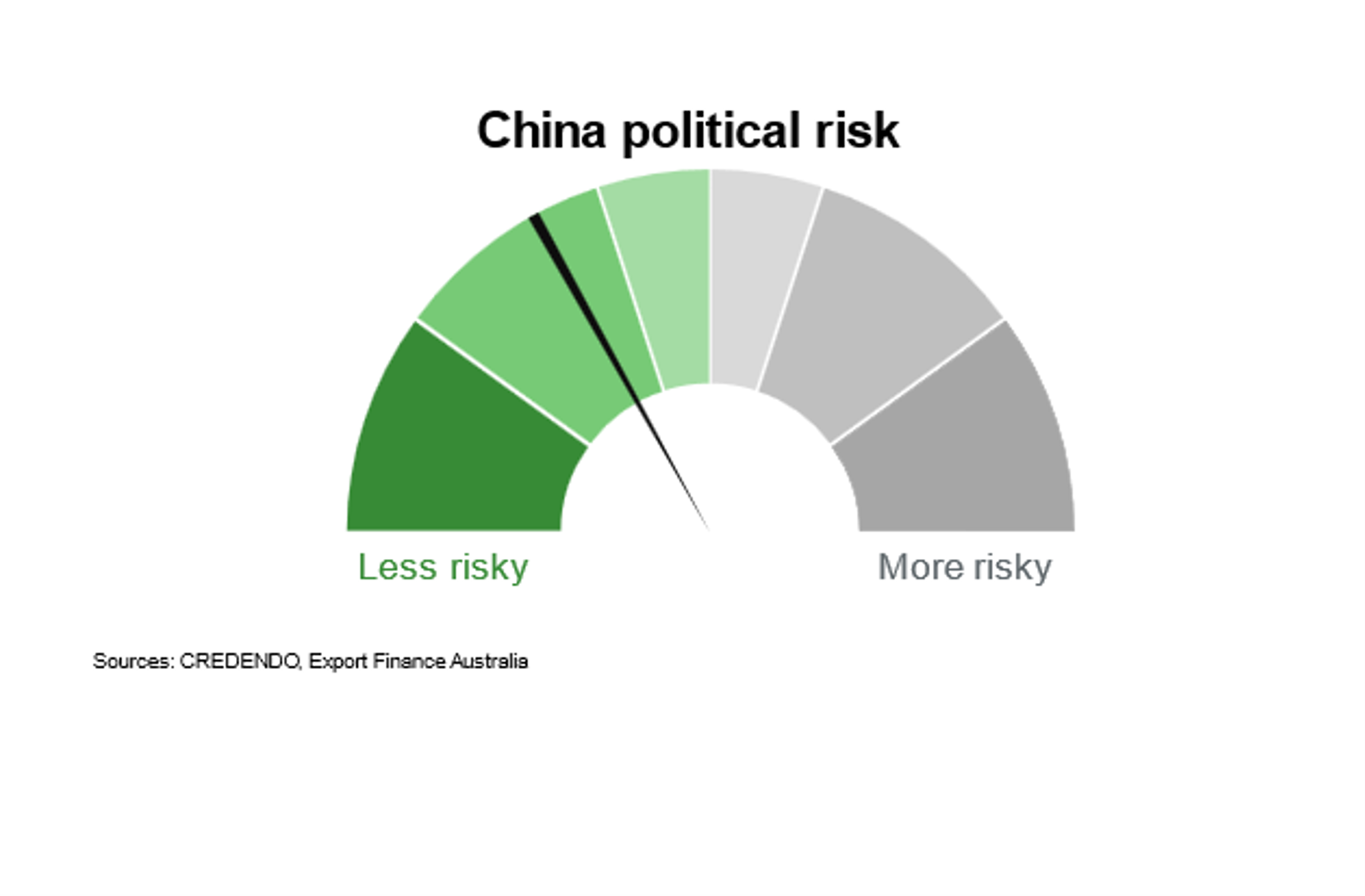

China’s political risk is on par with its overall rating. Political risk relates to the potential for further strain in geopolitical relations, including between China and the US and other countries, that adds to trade and growth risks.

China ranks higher or broadly in line with regional peers on most dimensions of governance, according to Worldwide Governance indicators. Government effectiveness is ranked near the top quartile, in part reflecting the effectiveness of government policies in helping to contain leverage and credit risks while also preserving economic, financial and social stability. China scores in the lowest quartile for voice and accountability.

Bilateral relations

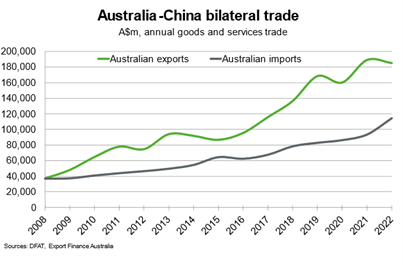

China is Australia’s largest export and import partner. Total goods and services trade amounted to $299 billion in 2022, around 25% of Australia’s global trade portfolio. Resources—iron ore and concentrates, natural gas, crude minerals, gold, copper and, aluminium ores and alumina—are Australia’s chief goods exports. Australian exports of agriculture to China (e.g. wheat, wool and beef) and services (e.g. tourism, aged care and education) are also significant. China’s rising middle class should support demand for Australian agriculture and services exports moving forward. On the downside, disruptions in trade with China remains a notable risk to some Australian resources and agriculture exporters. Australia’s major imports from China include household products, telecom equipment and parts, passenger motor vehicles, and electrical machinery and parts.

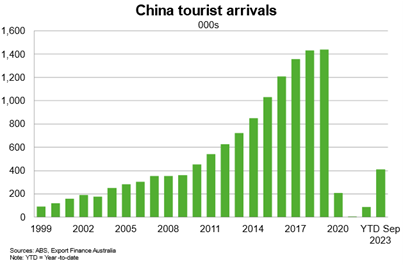

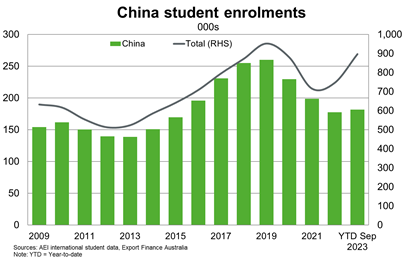

In the year to September 2023, China was Australia’s 4th largest source of tourist arrivals and largest source of student enrolments. That said, China’s exit from its zero-COVID policy in early 2023 has contributed to a delayed recovery in tourism arrivals and student enrolments. However, a competitive Australian dollar, recovery in Chinese group travel and another year of growth in international travel should support further demand for Australian tourism, and broader services exports, in 2024.

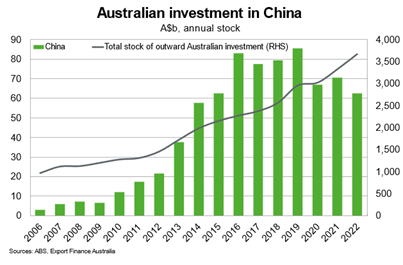

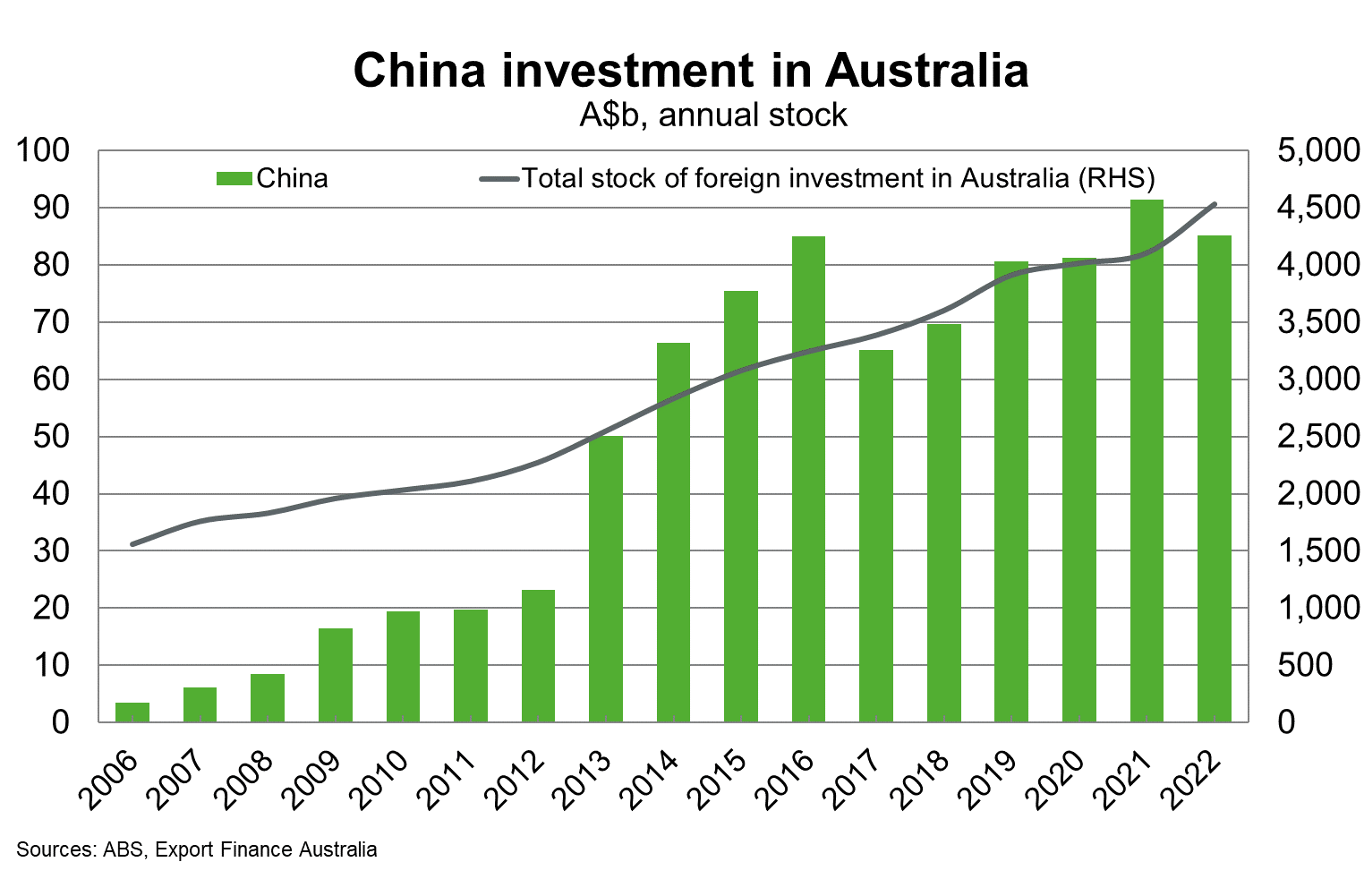

China is Australia’s 10th largest investor, owning a portfolio of $85 billion in 2022. In recent years, Chinese investment has broadened from resources and energy to sectors such as infrastructure, real estate, services and agriculture. The US ($1.1 trillion) and UK ($1 trillion) remained the largest investors in Australia in 2022.

Australian investment stocks in China fell to $62.5 billion in 2022 from $70.5 billion in 2021, continuing a downward trend since 2019. Businesses remain attracted to China’s growing economy and large domestic consumer market. Australia’s expertise in banking and wealth management services has seen financial institutions become some of the largest Australian investors in China.