Iran

Last updated: February 2022

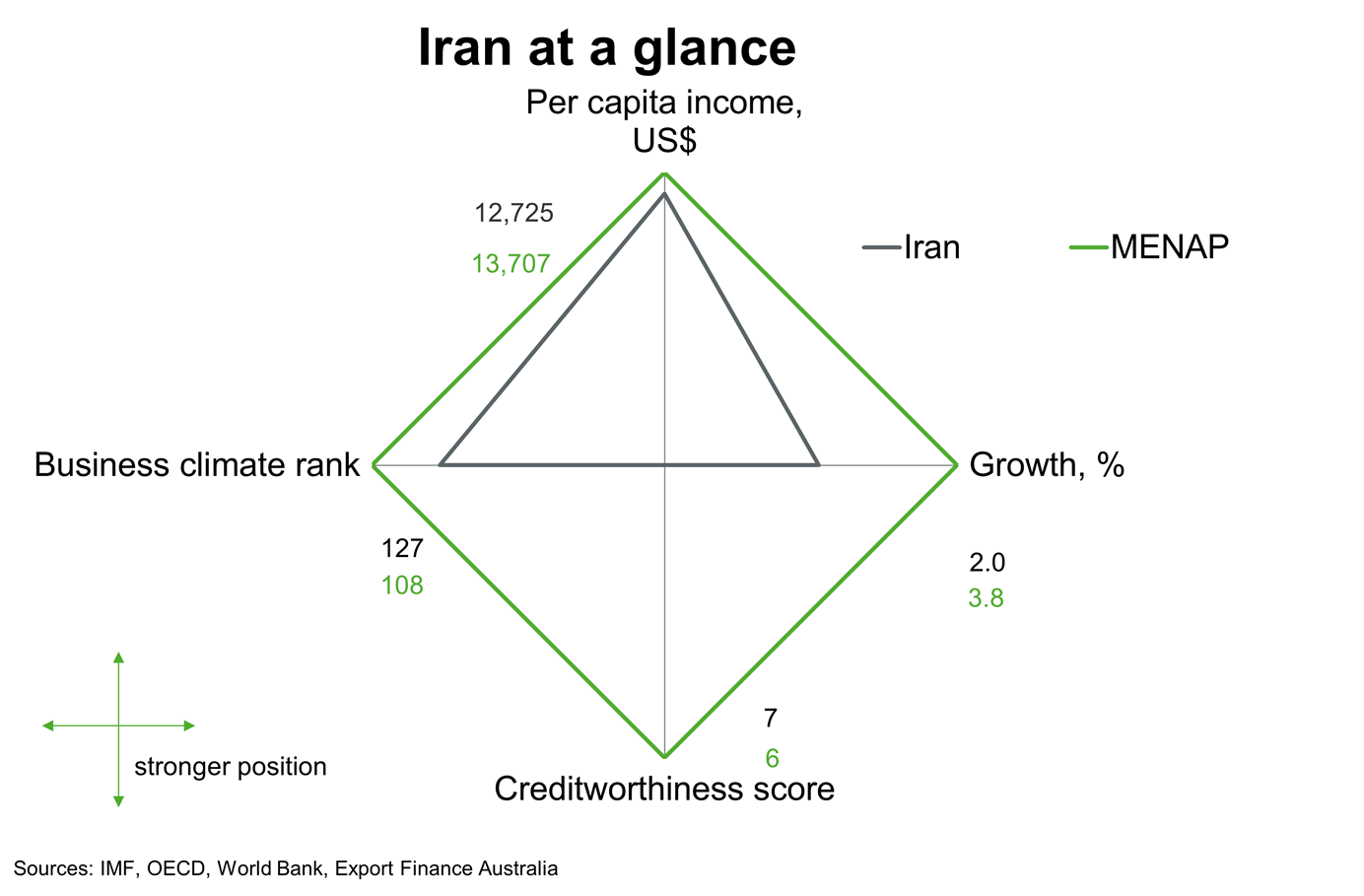

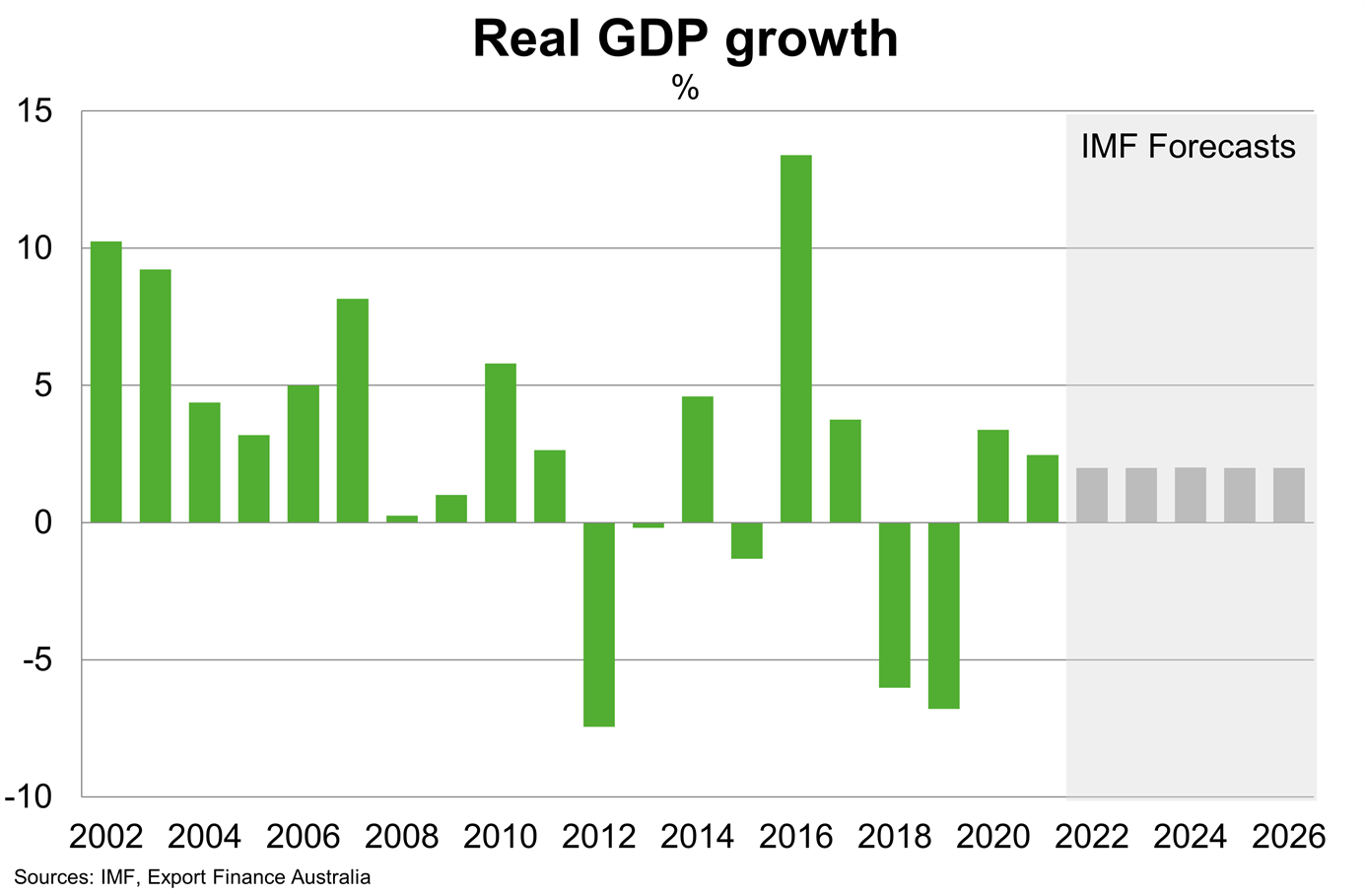

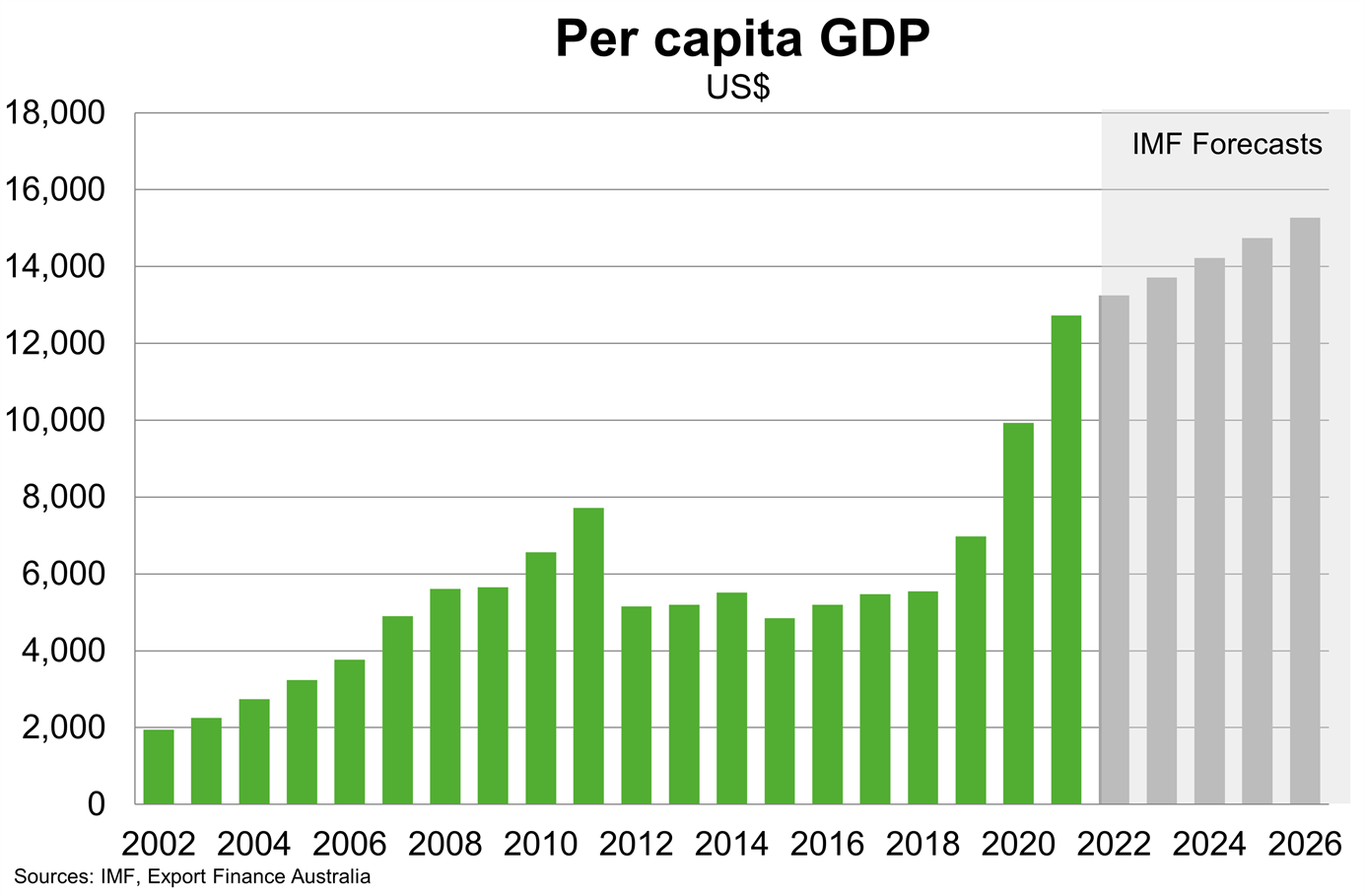

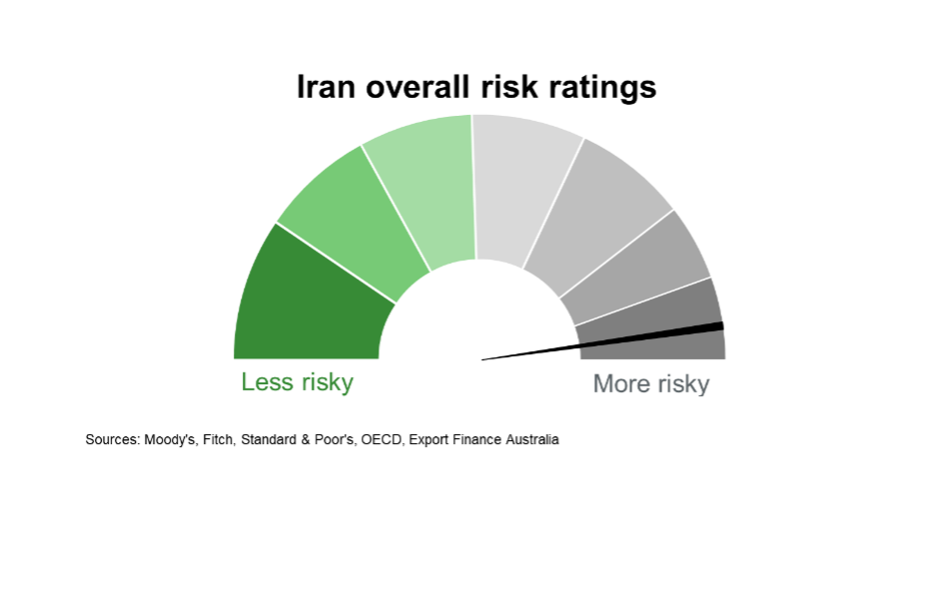

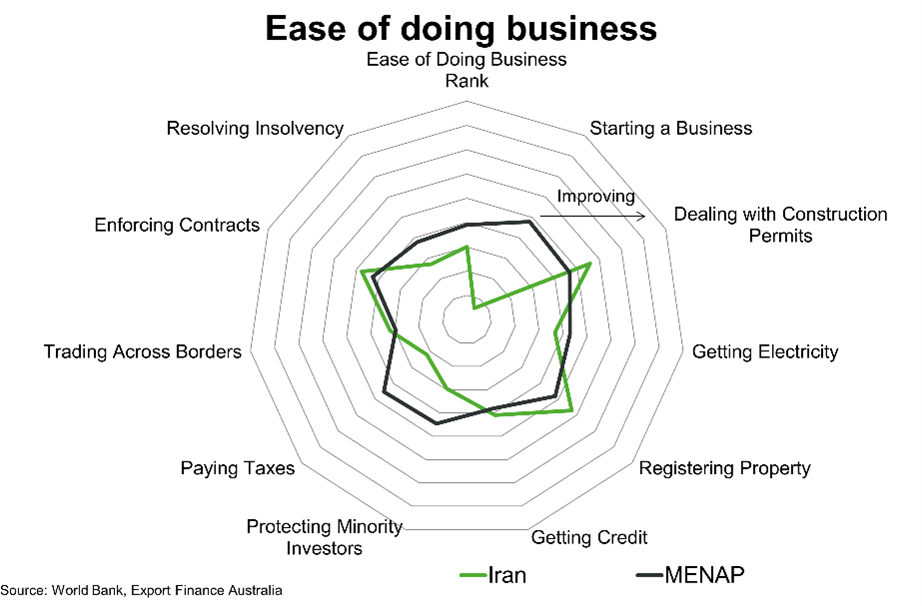

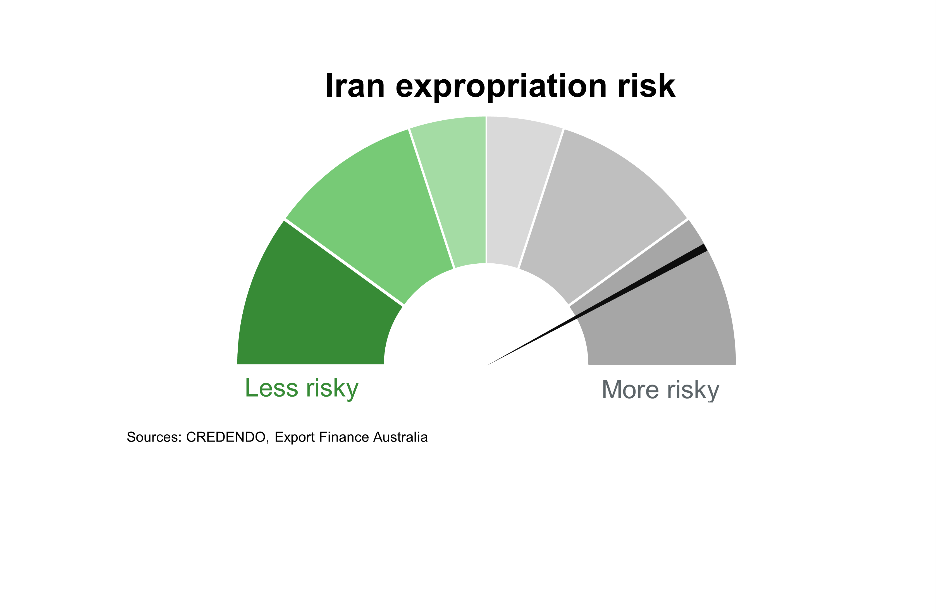

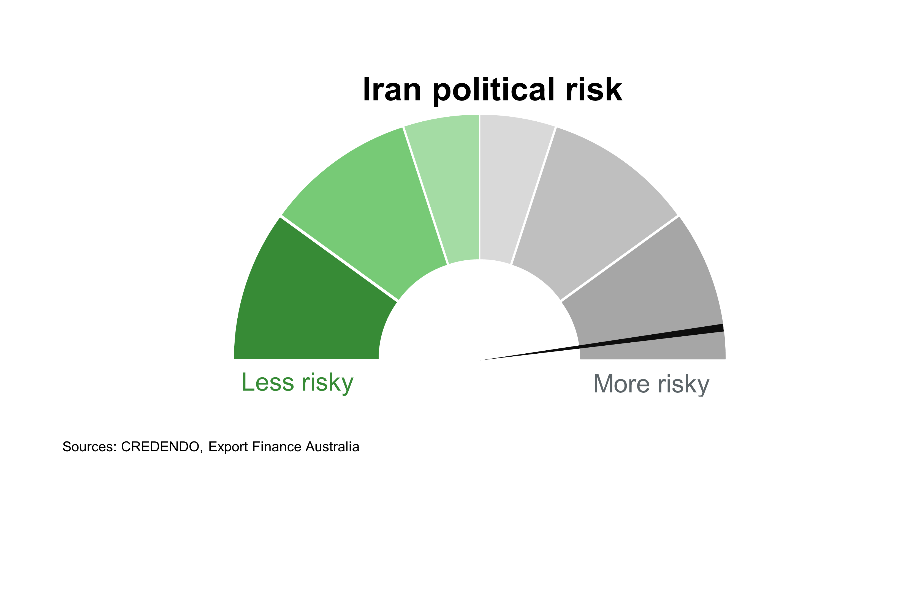

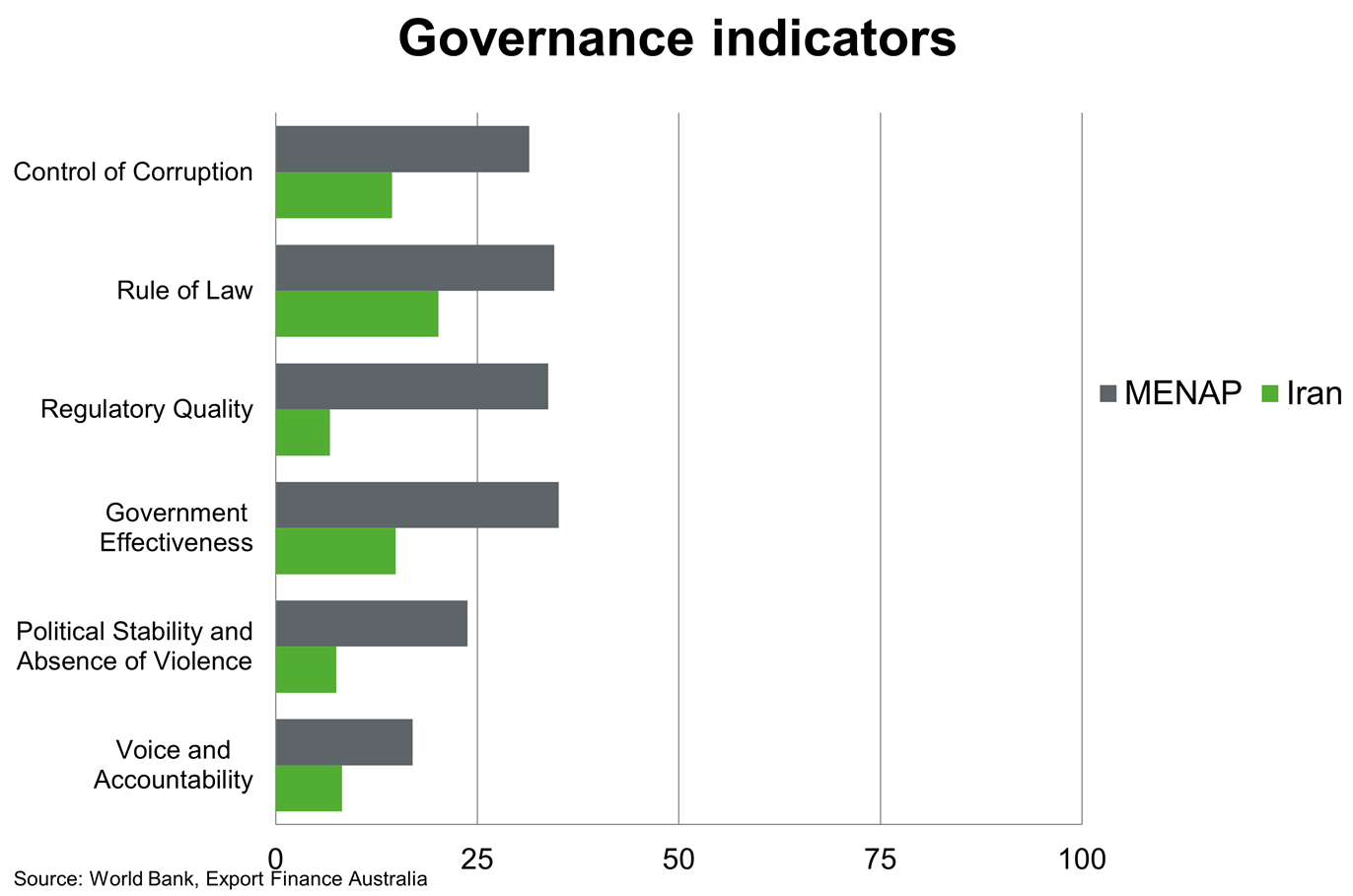

Iran lags most Middle Eastern countries on measures of growth, per capita incomes, business climate and creditworthiness. The economy is recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic but international sanctions remain a constraint on oil exports. Inflation remains high because of import restrictions and sharp currency depreciation in recent years.