Malaysia

Malaysia

Last updated: January 2024

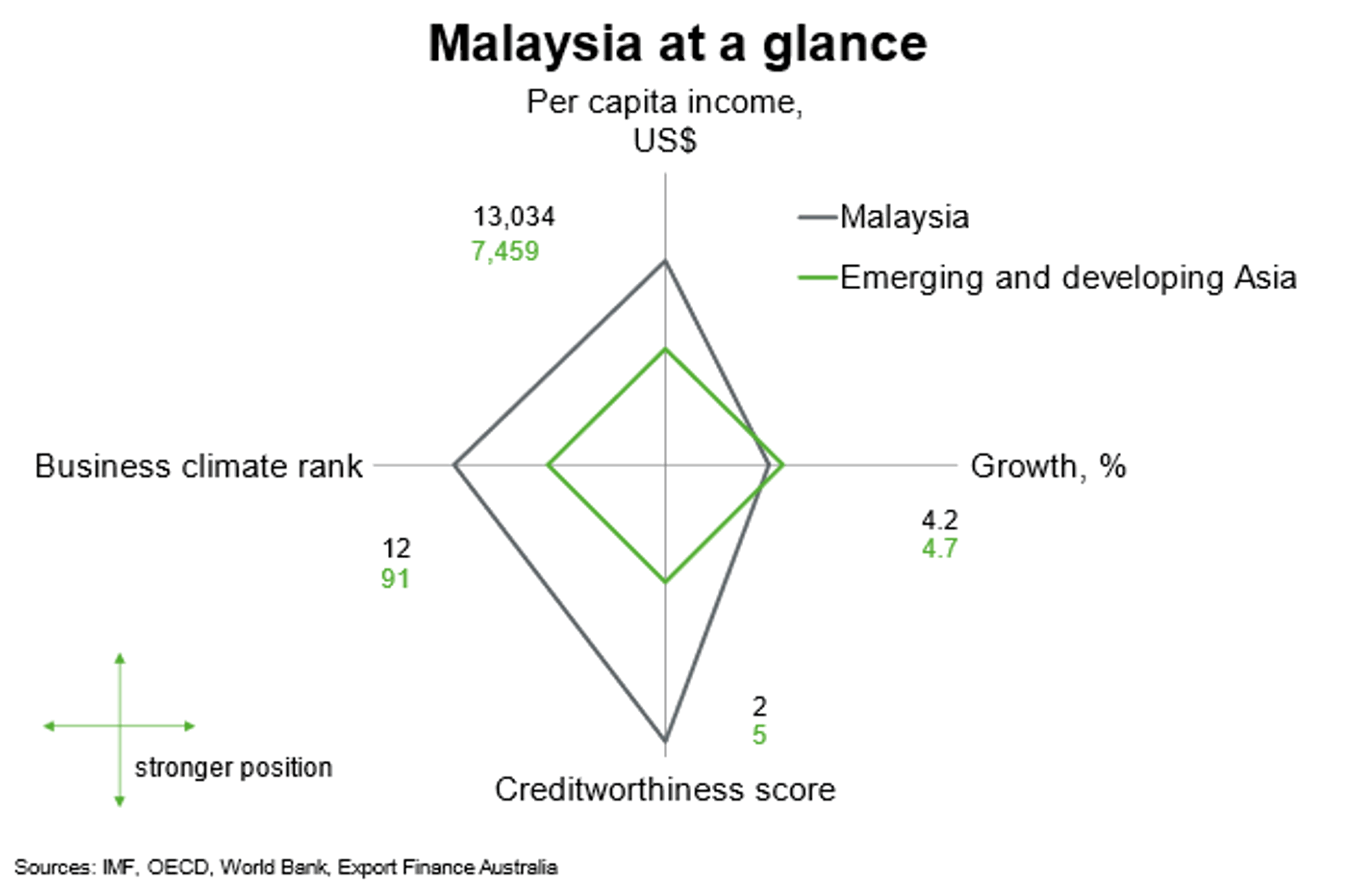

Malaysia has a strong economic development record. Since independence in 1957, Malaysia has expanded manufacturing, services and tourism industries to complement the country’s competitive resource sector. It is an upper middle-income, export-oriented economy. Relative to emerging and developing Asia, Malaysia has stronger creditworthiness, higher per capita incomes and a more conducive business environment, while GDP growth slightly lags its peers.

This chart is a cobweb diagram showing how a country measures up on four important dimensions of economic performance—per capita income, annual GDP growth, business climate and creditworthiness. Per capita income is in current US dollars. Annual GDP growth is the five-year average forecast between 2024 and 2028. Business climate is measured by the World Bank’s 2019 Ease of Doing Business ranking of 190 countries. Creditworthiness attempts to measure a country's ability to honour its external debt obligations and is measured by its OECD country credit risk rating. The chart shows not only how a country performs on the four dimensions, but how it measures up against other regional countries.

Economic outlook

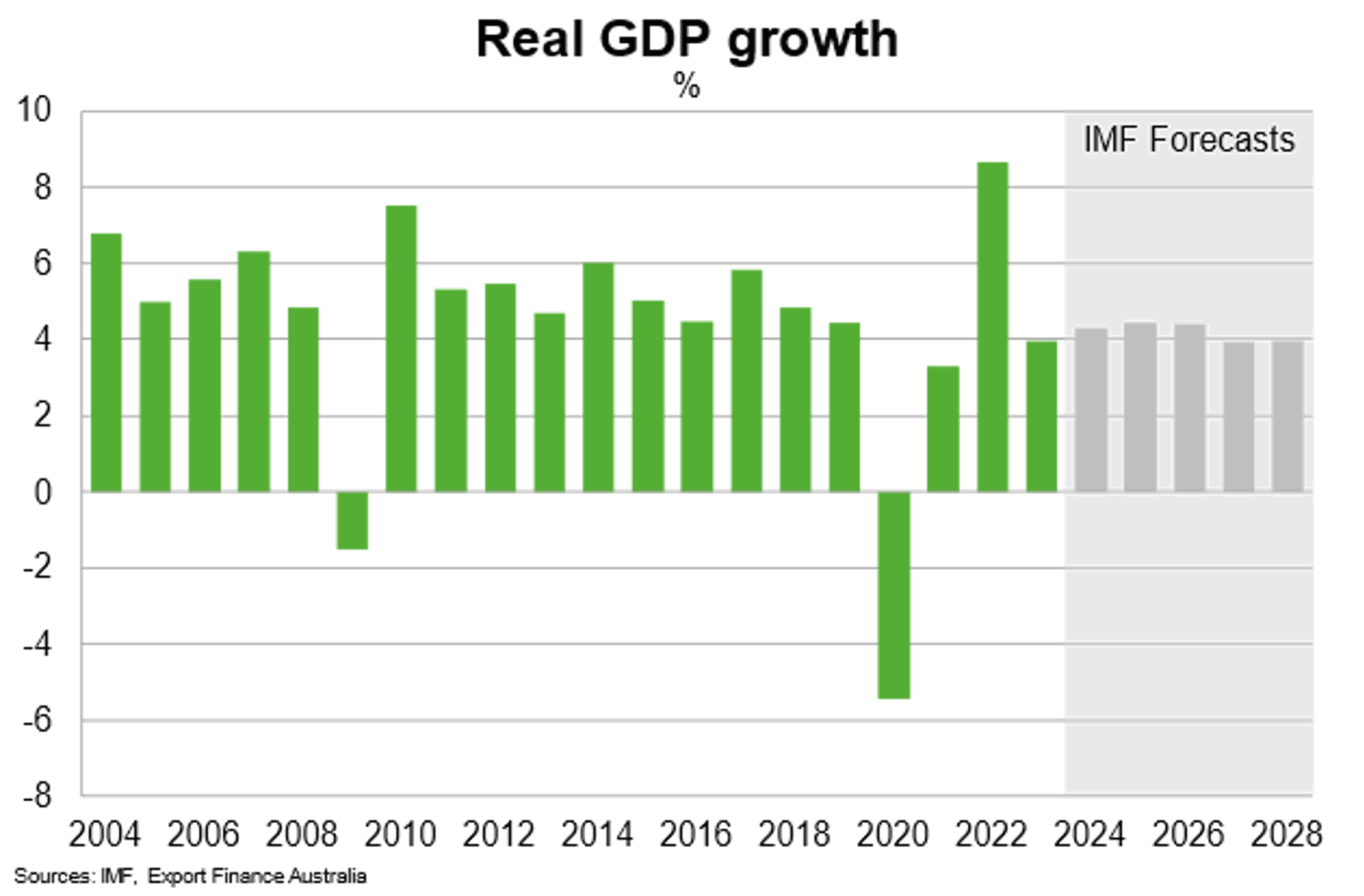

The Malaysian economy grew 3.7% in 2023 under IMF estimates, down from 8.7% in 2022. Growth remains robust despite external headwinds that have dampened exports, including weaker Chinese electronics demand and softer international resources and energy prices. Private consumption remained a key contributor of growth, supported by a healthy labour market. Subsidies in petrol, cooking oil, rice and other items through 2023 helped control inflation and alleviate pressures on household budgets.

The IMF expects real GDP growth of 4.3% in 2024. In the near-term, growth will hinge on continued resilience of private consumption, alongside a rebound in investment and efficient public spending. The budget is on a fiscal consolidation path to put debt on a downward trajectory; the government aims to remove subsidies and implement new taxes to create spending space for critical investment needs and targeted transfers to low-income households. The exports sector is likely to remain challenged by lower commodity prices, plans to ban exports in critical minerals and a slowdown in China’s economy.

External risks to the outlook reflect the potential for a sharp decline in global growth, which would hurt external demand. Middle East tensions and other geopolitical tensions could disrupt shipping. On the domestic front, political tensions remain an ongoing risk to implementation of important reforms.

In the longer term, favourable demographics and an expanding middle class bode well for raising consumption growth. The IMF expects GDP growth to average 4.2% between 2025 and 2028. The government’s long-term development plan called Shared Prosperity Vision 2030, if successfully implemented, will raise labour skills, reduce wealth and income disparities and combat corruption, helping to enhance the business environment. This will be further supported by policy initiatives under the Madani economy framework, including to boost education and raise incomes, among others accompanying national strategic plans.

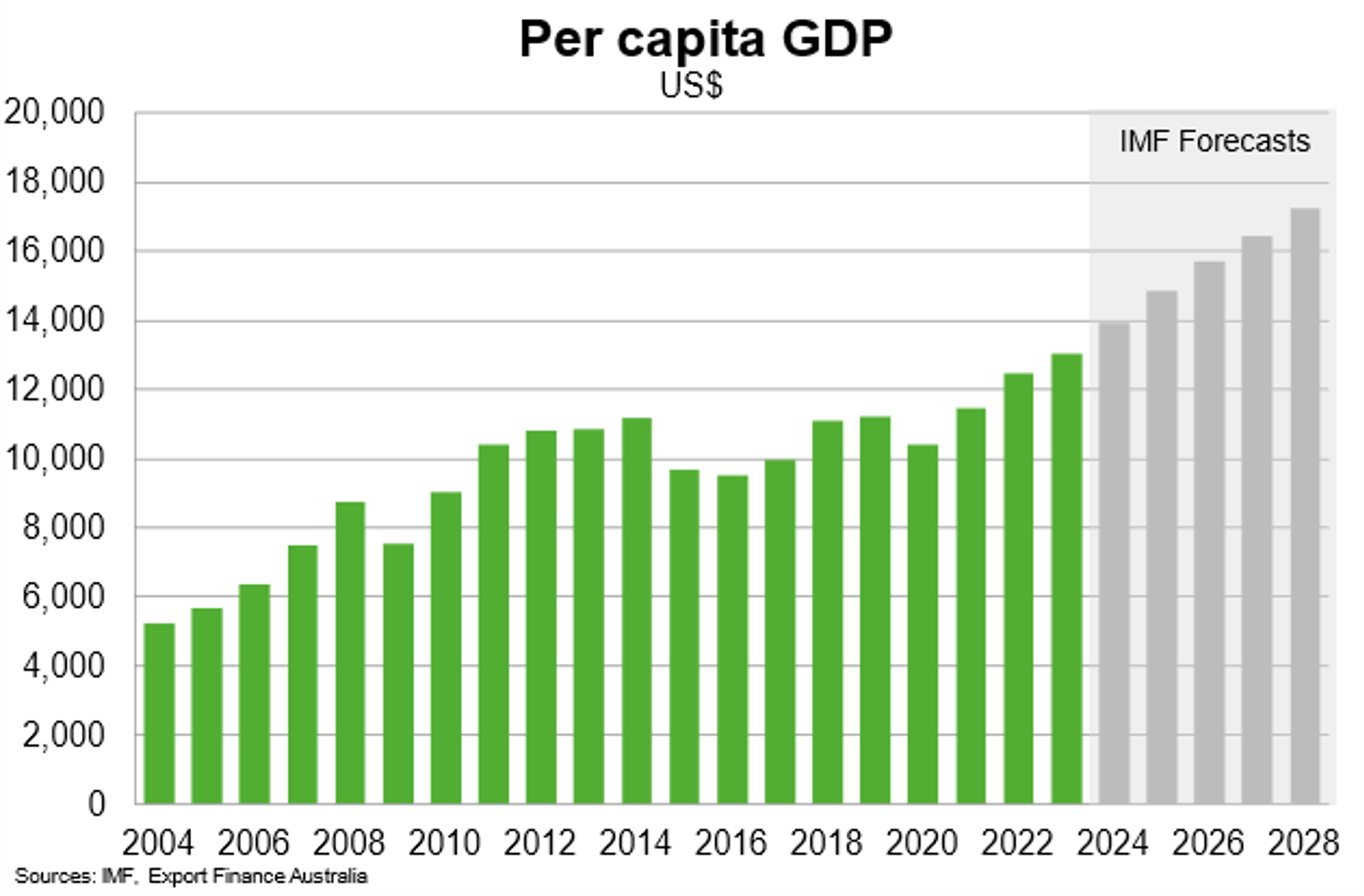

Malaysia is classified as an upper-middle income economy by the World Bank, with GDP per capita estimated at about US$13,000 in 2023. Economic growth is strengthening Malaysia’s job market, reducing the unemployment rate (to 3.3% in January 2024) and supporting incomes. The World Bank expects Malaysia’s ongoing development plans to help the economy reach high-income status between 2024 and 2028

Country Risk

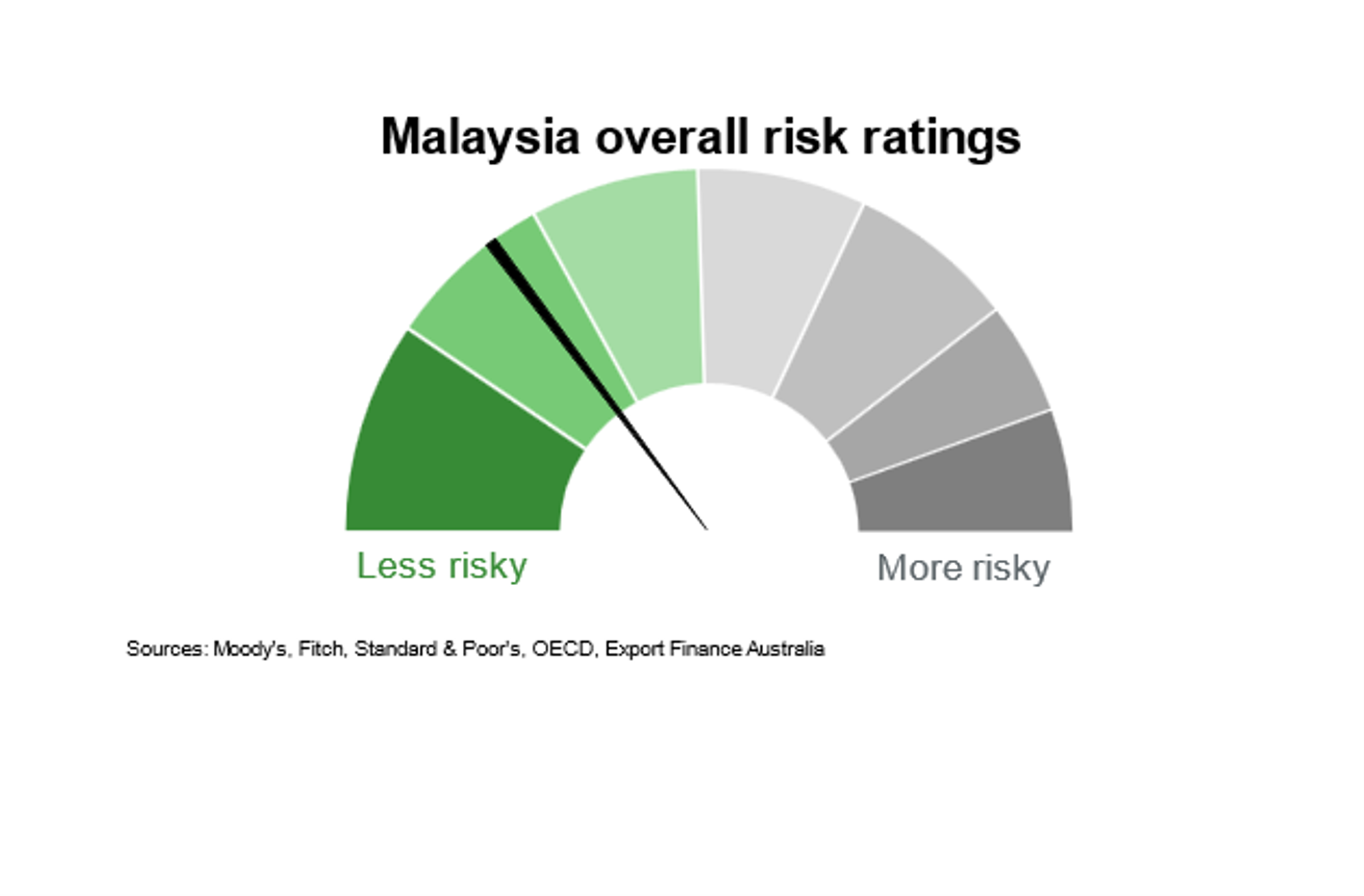

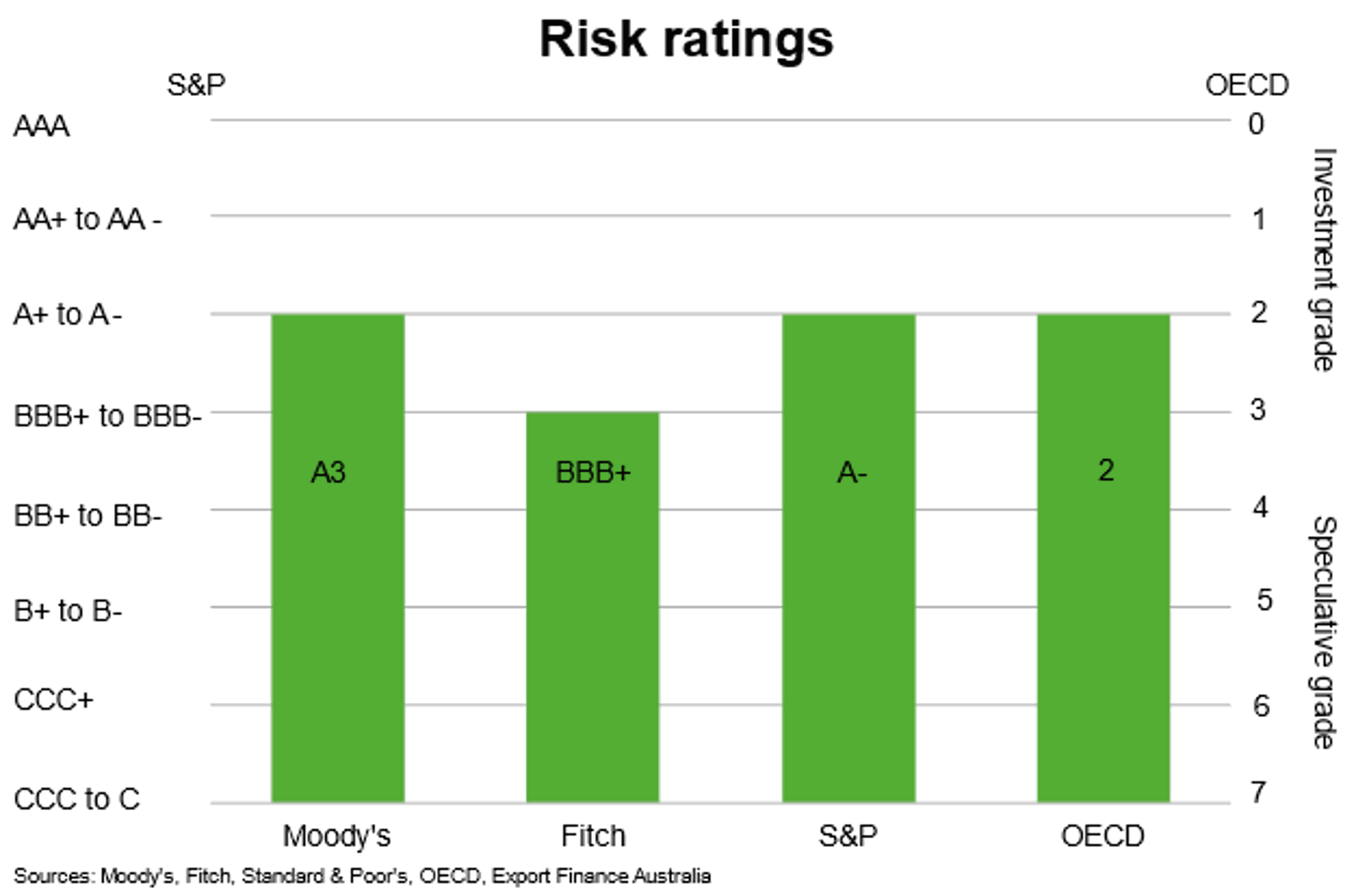

Country risk in Malaysia is low. Malaysia has investment grade credit ratings from major private credit rating agencies. Malaysia has an OECD Country Grade of 2, which is higher than many of its peers in Asia. This means the likelihood that Malaysia is unable to service its debt obligations is low.

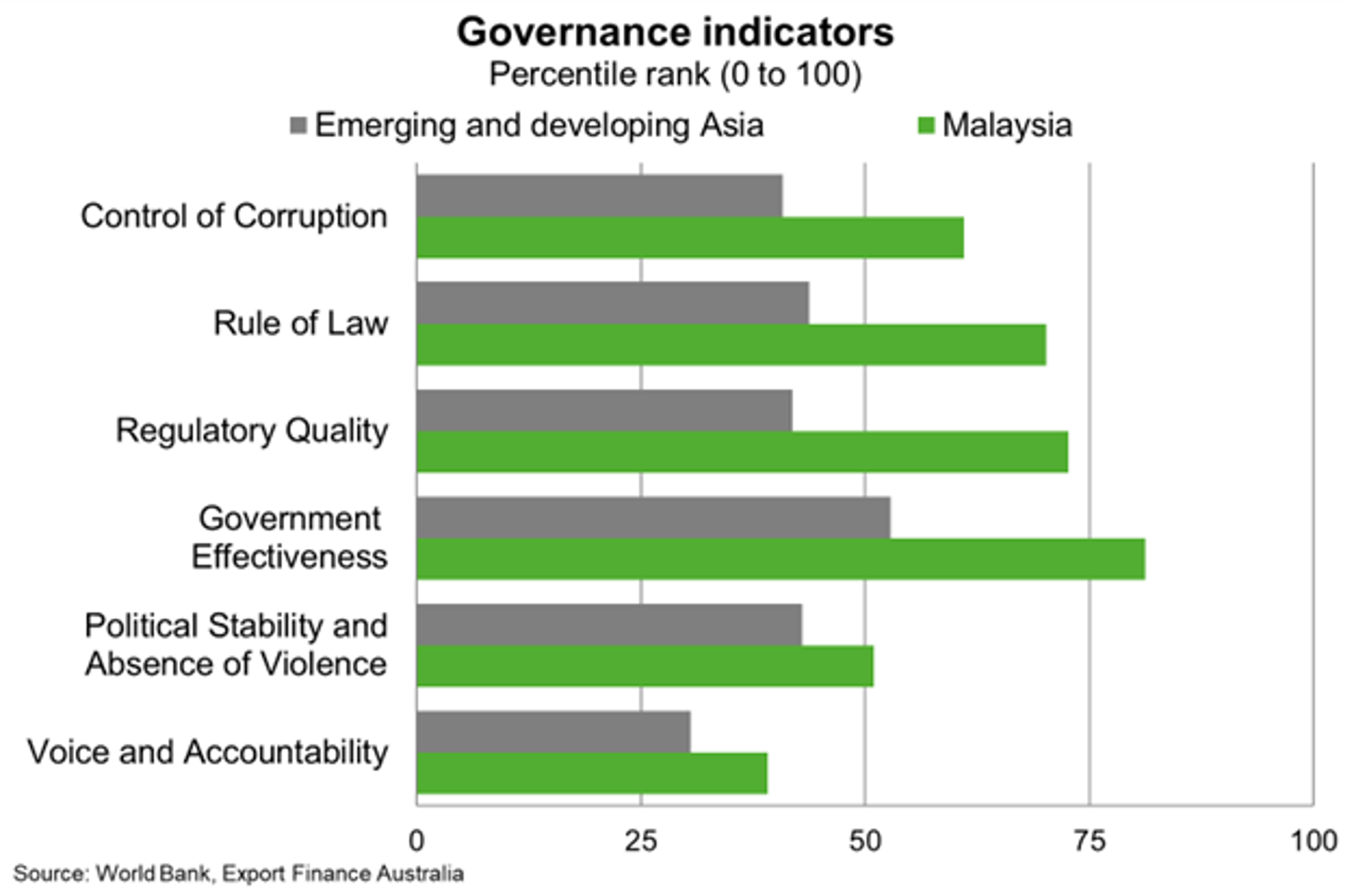

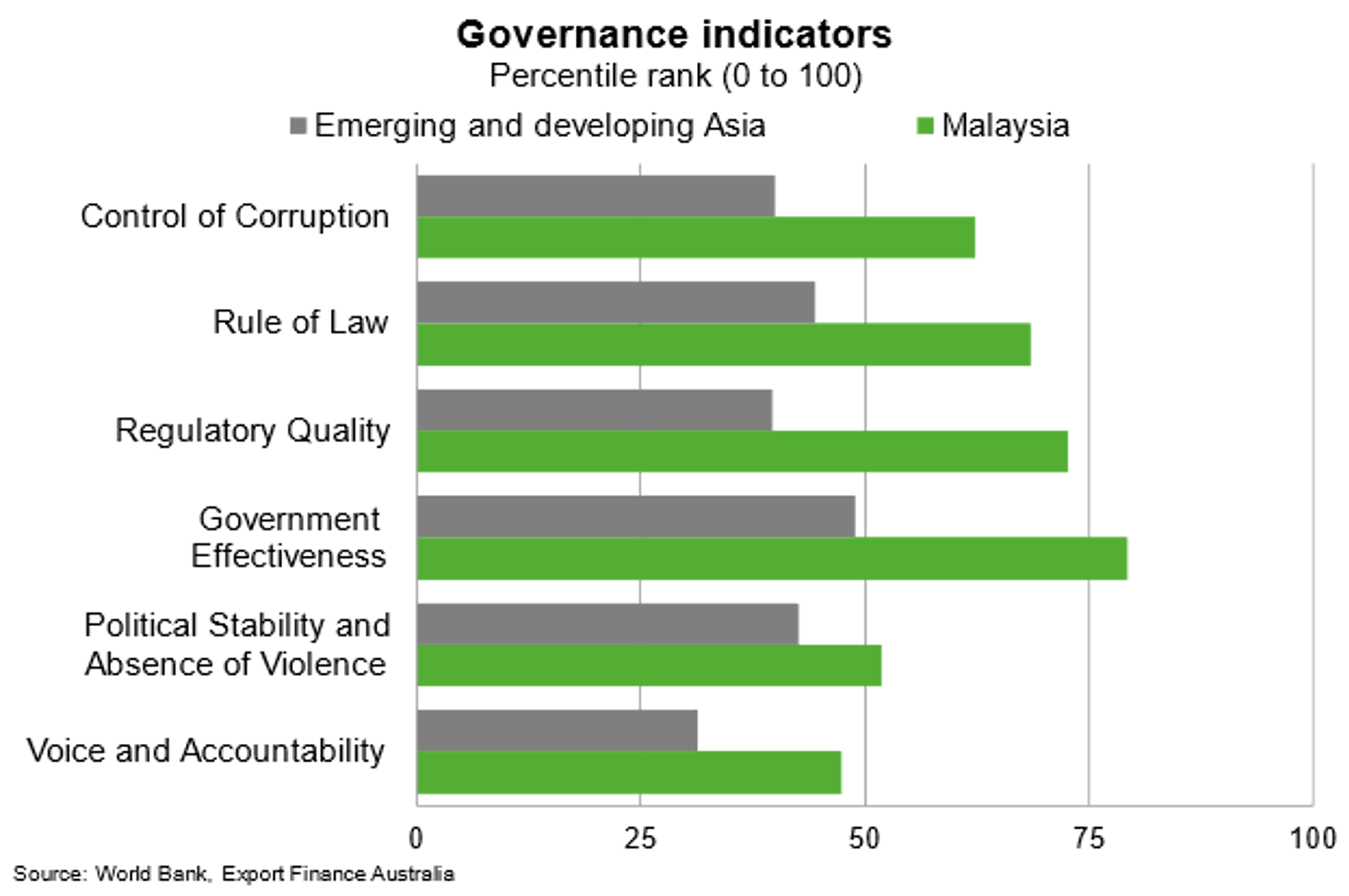

Malaysia’s high scores on governance indicators, particularly government effectiveness and regulatory quality, point to strong governance and institutional frameworks on a stand-alone basis and relative to other emerging and developing Asian countries. Most governance indicators are in the top 50th percentile, except for voice and accountability.

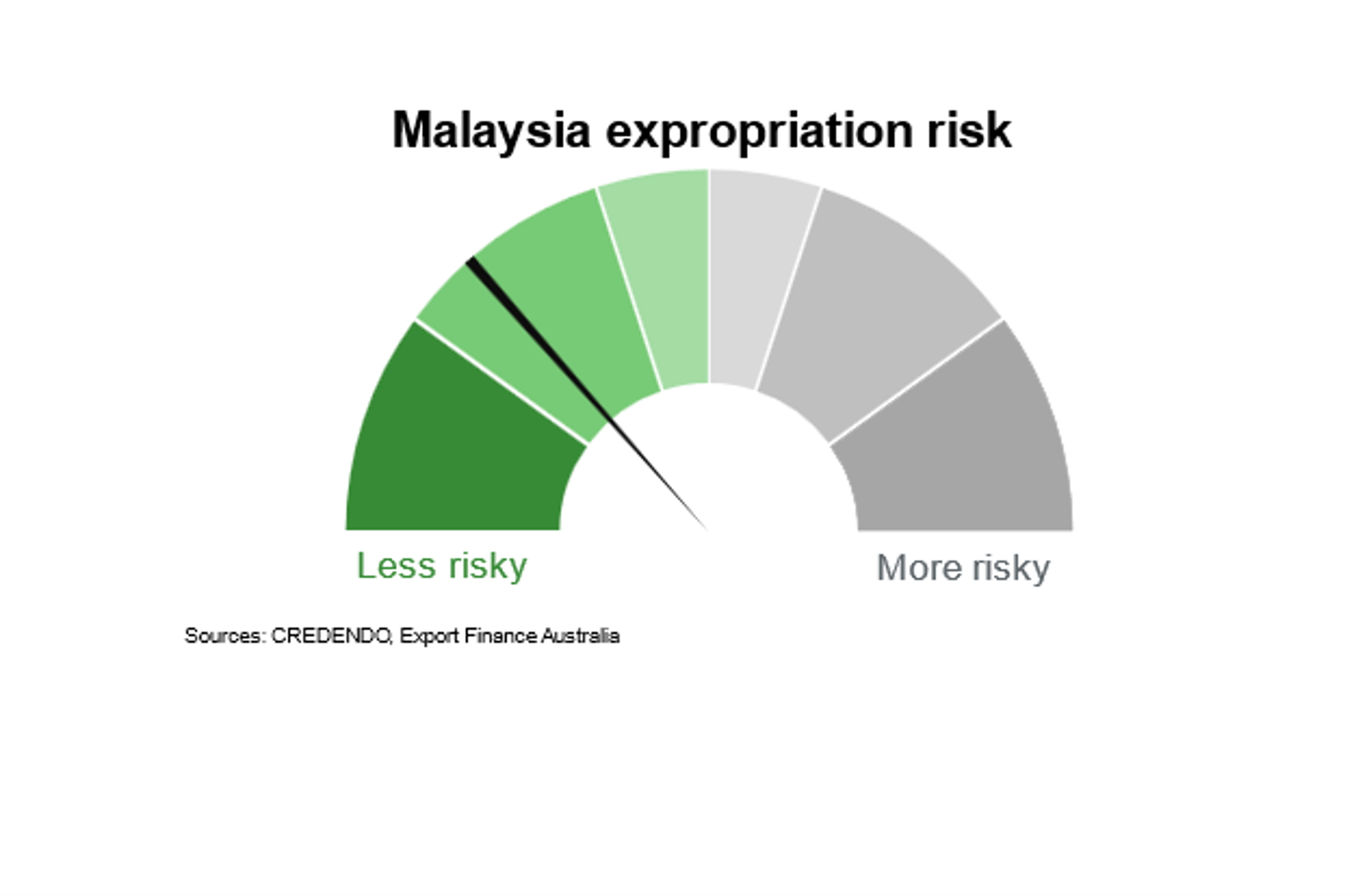

The risk of expropriation in Malaysia is low. Government policies indicate that all investors, both foreign and domestic, are entitled to fair compensation in the event that their private property is required for public purposes. The judicial system is generally regarded as free from political interference.

The risk of expropriation in Malaysia is low. According to the US Investment Climate Statements, government policies indicate that all investors, both foreign and domestic, are entitled to fair compensation in the event that their private property is required for public purposes. The judicial system is generally regarded as free from political interference.

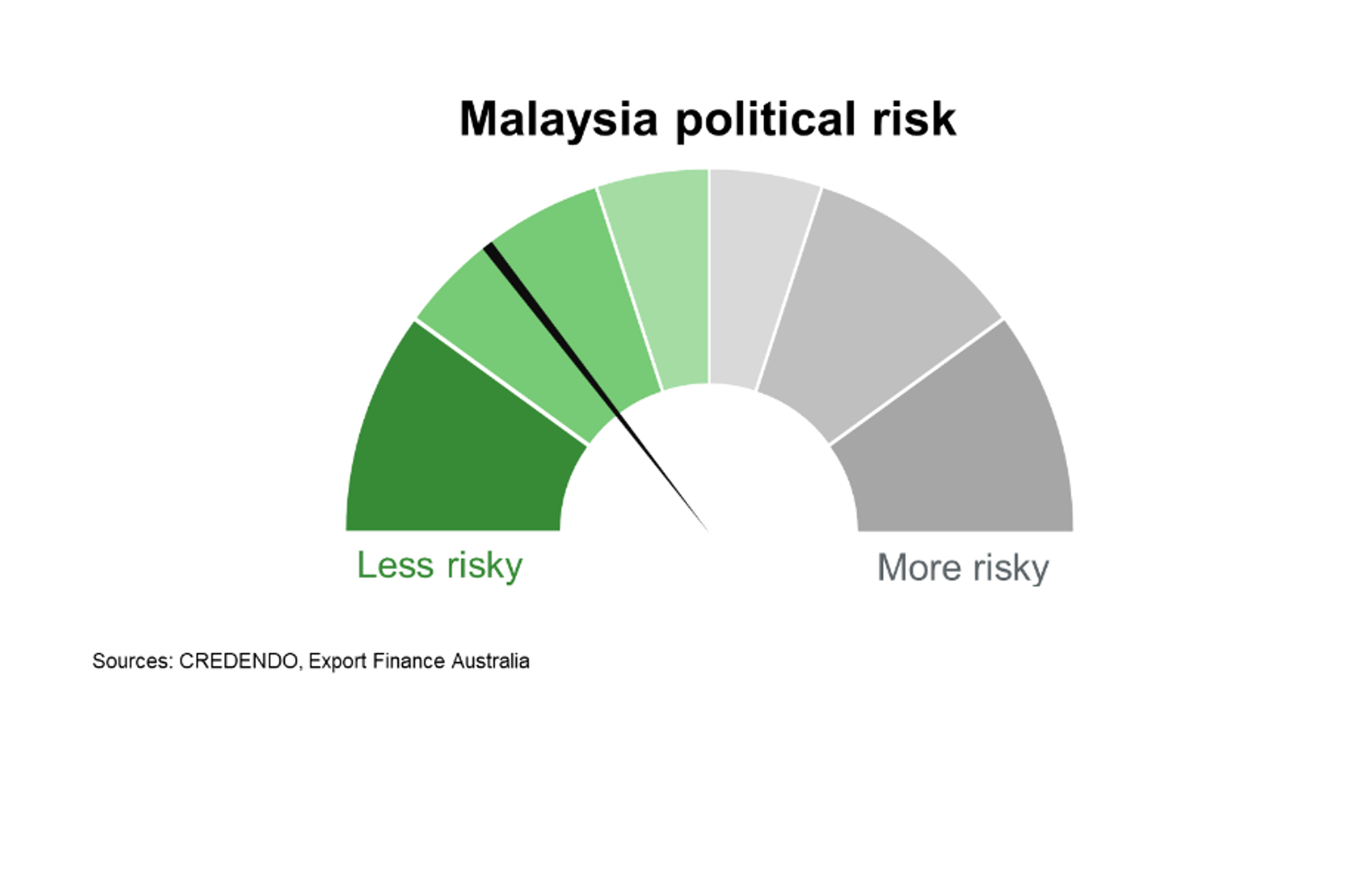

Political risk in Malaysia is low. Political tensions—which reflects a ruling coalition of multiple parties—remains a risk to the implementation of some necessary yet politically difficult reforms.

Bilateral Relations

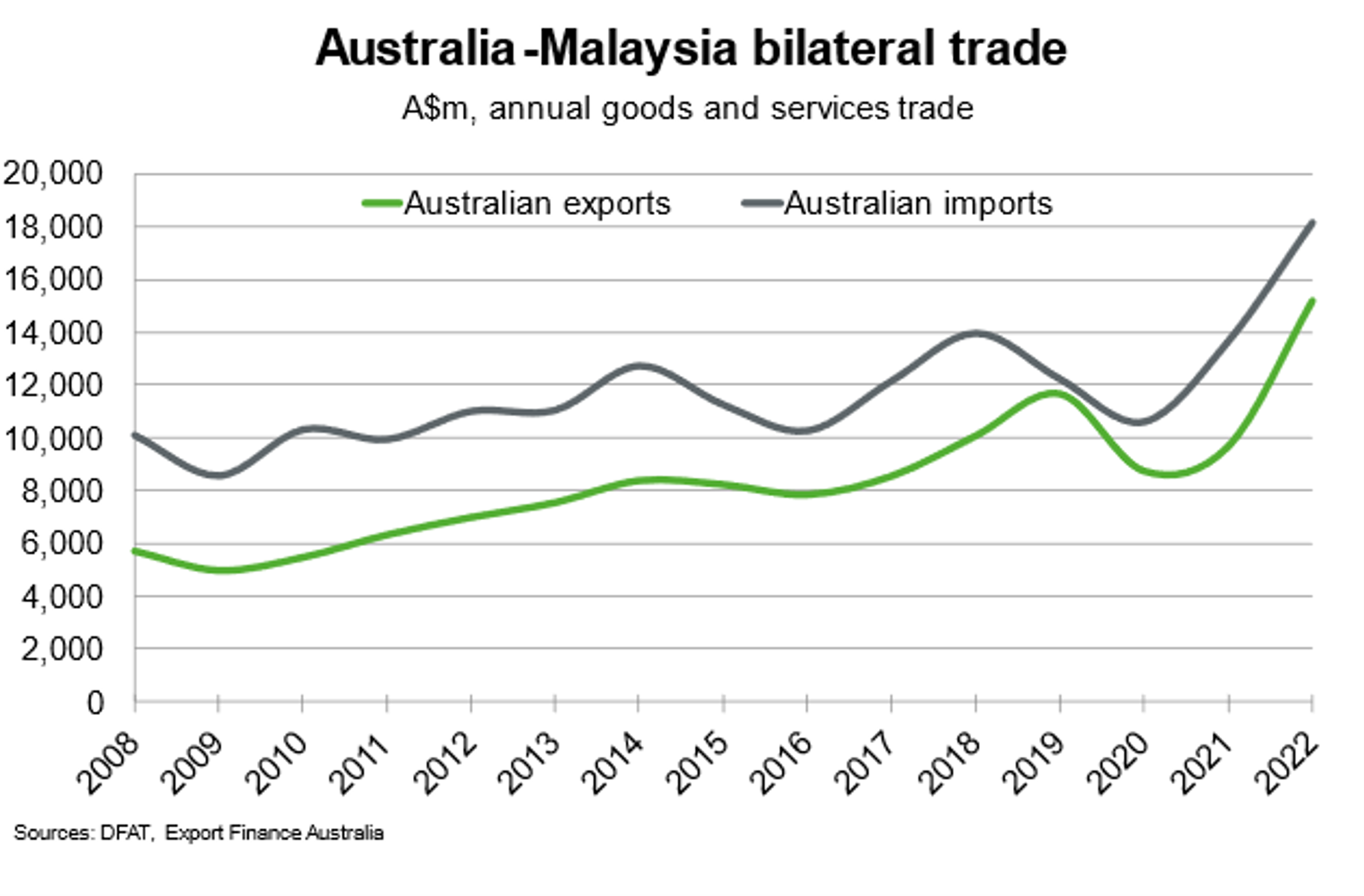

Malaysia was Australia’s 8th largest trading partner in 2022, accounting for around $33.4 billion or 2.8% of Australia’s bilateral trading relationship. Major Australian goods exports to Malaysia in 2022 included coal, natural gas, copper and education-related travel. Major Australian goods imports included crude and refined petroleum, computers, telecommunications equipment and electronics.

It is estimated, more than 3,800 Australian businesses trade with Malaysia, around 300 of which have a physical presence in the country. Malaysia’s growing economy presents opportunities for Australian exporters of food and agribusiness, education, health care, digital economy (e-commerce and fintech), infrastructure and resources and energy.

More broadly, the Australia–Malaysia economic relationship is underpinned by a common interest in a free and open trading system, and two free trade agreements (FTAs)—the Malaysia–Australia FTA (MAFTA) and the ASEAN–Australia–New Zealand FTA (AANZFTA). The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) adds further upside to the bilateral trade relationship.

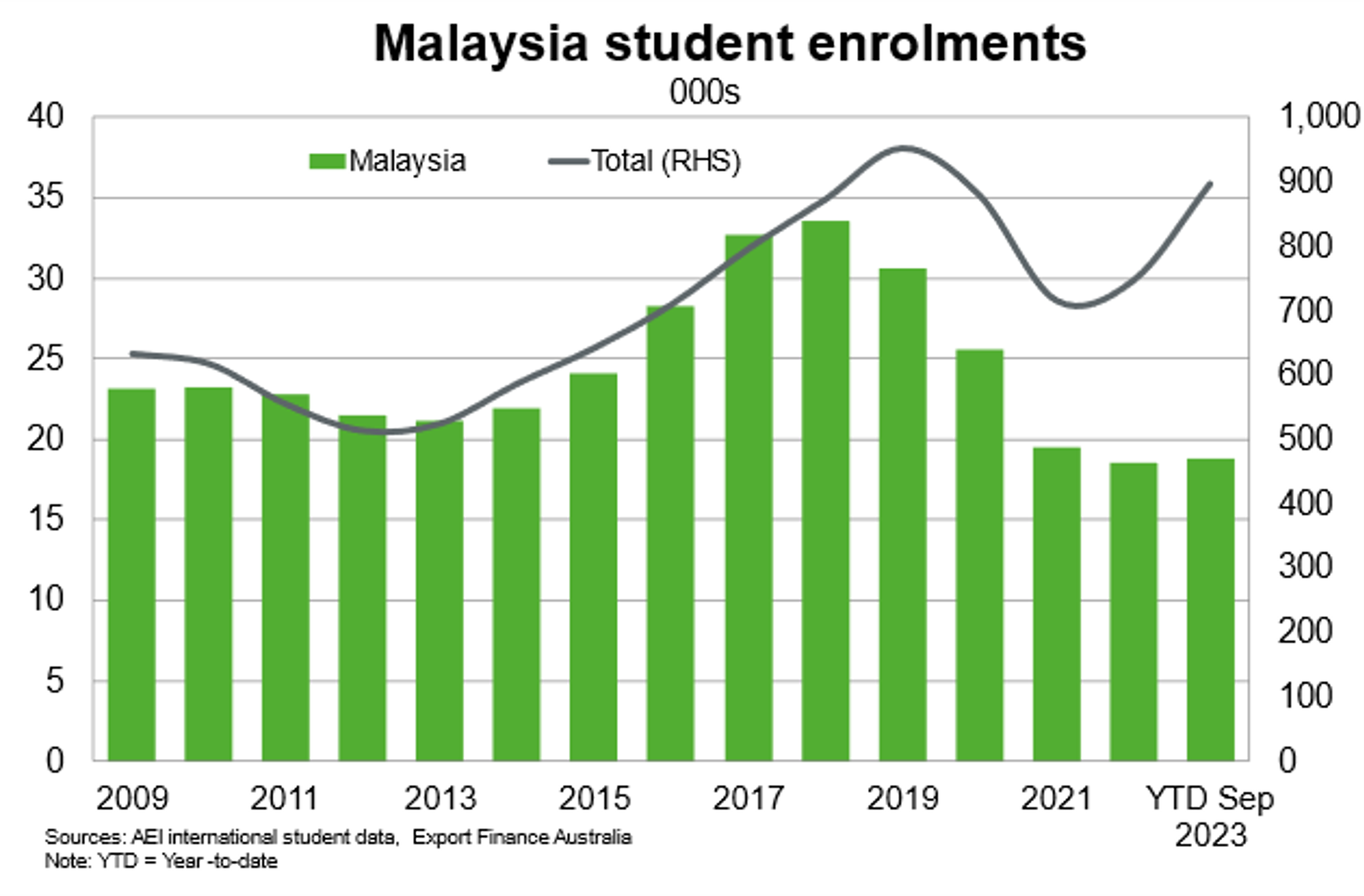

Malaysian student enrolments rose marginally over the year to September 2023. This comes after a steady fall in enrolments since 2018, reflecting a growing preference among Malaysian students to study locally amid improving domestic institutions and the effects of the pandemic. Malaysia was Australia’s 11th largest source of international students as of September 2023, down from sixth in 2018.

Tourism’s recovery from the pandemic has been sluggish following Malaysia’s opening of international borders in April 2022. Increasing domestic tourism and consumption may reflect a growing preference among Malaysian’s to travel locally, particularly as a depreciating Malaysian ringgit makes international travel more expensive. Looking ahead, a competitive Australian dollar and another year of recovery in international travel should support demand for Australian tourism, and broader services exports, in 2024.

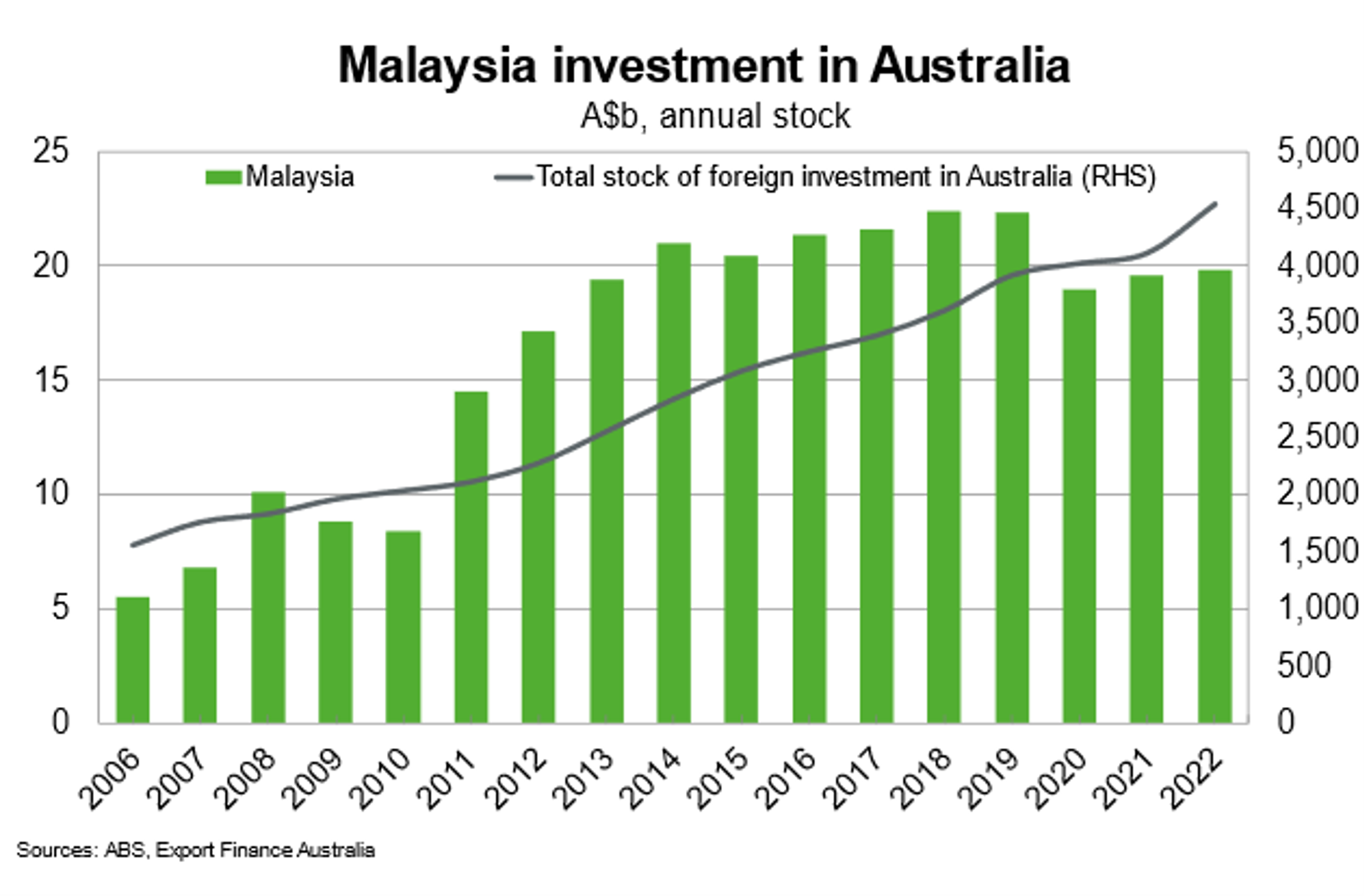

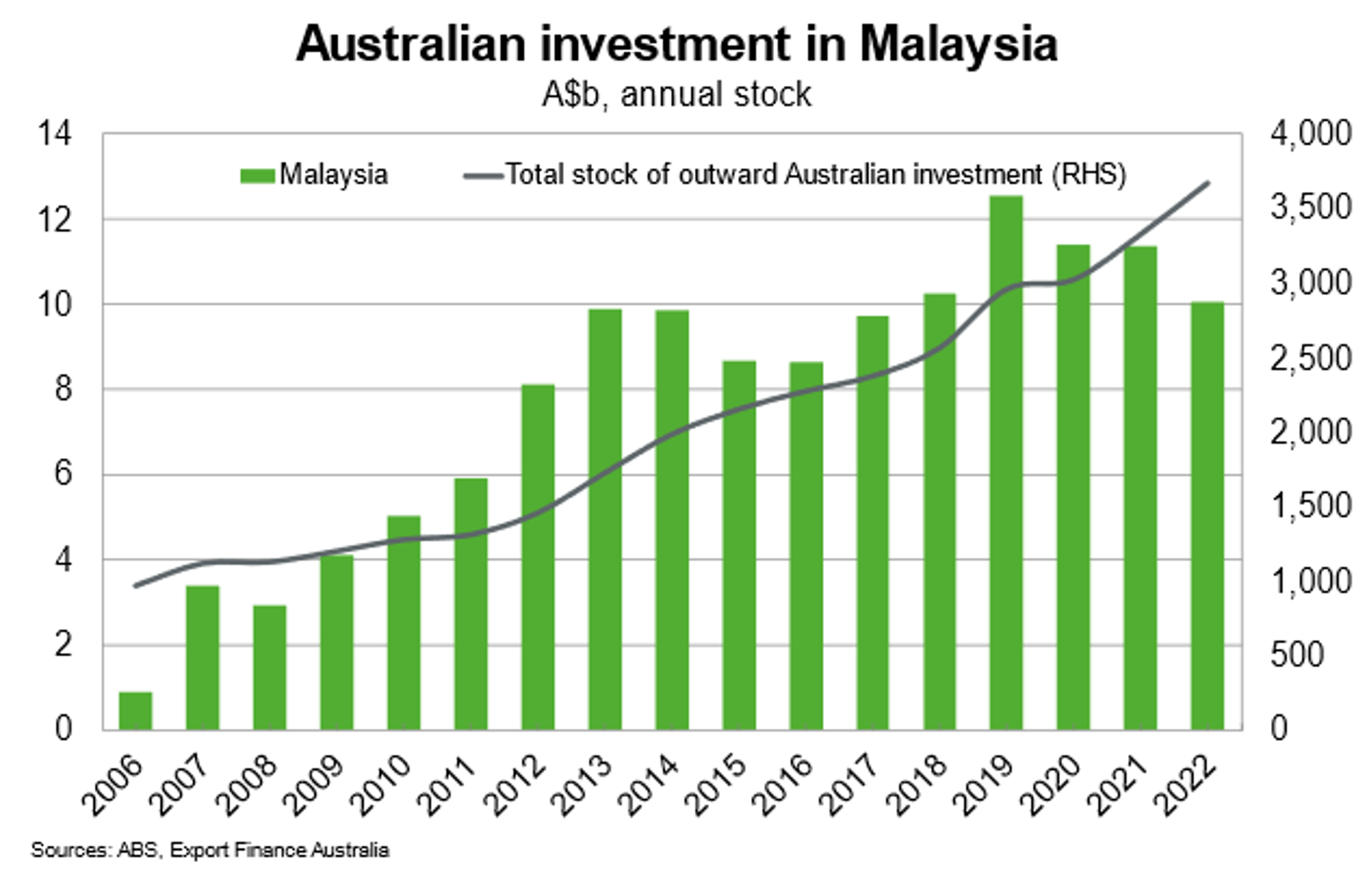

In terms of foreign investment stocks, Malaysia is a modest investor in Australia, owning a portfolio of $20 billion in 2023 (0.4% of the total foreign investment stock). Malaysian investment is focused on Australian property, tourism infrastructure, energy and resources and food and agribusiness. Malaysia constituted a small share of Australia’s investment abroad at $10 billion in 2022 or 0.3% of the total stock of outward investment. The Australia-Malaysia Tech Exchange (AMTX), launched in May 2021, is helping Australian exporters expand their e-commerce presence in Malaysia and promote two-way investment.