South Korea

Last updated: February 2024

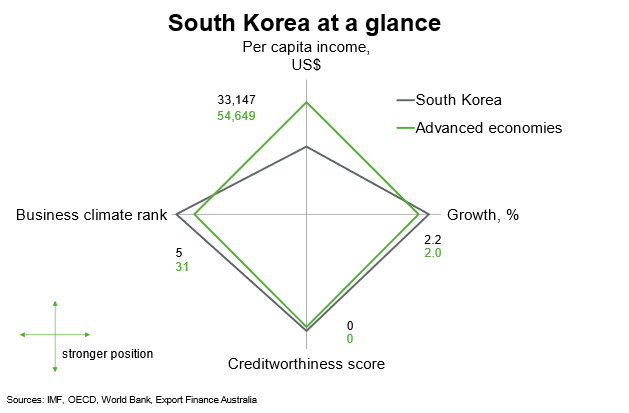

South Korea is the 13th largest economy in the world and the 4th largest in Asia. Per capita incomes are high, albeit they lag behind most advanced economies. The business environment is stronger than other advanced economies, while growth is broadly in line with peers. Creditworthiness is high, as is the case in many advanced economies.

The above chart is a cobweb diagram showing how a country measures up on four important dimensions of economic performance—per capita income, annual GDP growth, business climate rank and creditworthiness. Per capita income is in current US dollars. Annual GDP growth is the five-year average forecast between 2024 and 2028. Business climate is measured by the World Bank’s 2019 Ease of Doing Business ranking of 190 countries. Creditworthiness attempts to measure a country's ability to honour its external debt obligations and is measured by its OECD country credit risk rating. The chart shows not only how a country performs on the four dimensions, but how it measures up against other countries in the region.

Economic outlook

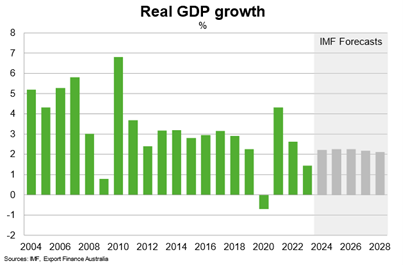

Real GDP grew at a three-year low of 1.4% in 2023, as global demand for electronics and semiconductors remained subdued and monetary policy tightening weighed on private consumption and investment. Inflation has gradually declined, but remains above the 2% target rate, in part due to higher import prices for global energy and food products. Interest rates remain at 3.5%, even as the housing market recovers.

The IMF forecasts growth to pick up to 2.3% in 2023, driven by recovery in electronics demand, continued stabilisation of the domestic housing market and an expected resumption in group tourism (the government plans to exempt visa issuance fees for group tourist from China and other Asian countries). Tight monetary policy and mildly restrictive fiscal policy are likely to weigh on private consumption and investment. Similarly, high household debt (at more than 100% of GDP) and elevated debt servicing costs are likely to continue to constrain economy-wide demand. Inflation is projected to approach the 2% target by the end of 2024, and reach the target in 2025.

Regarding risks, high energy prices, further supply chain disruptions and regional geopolitical tensions remain notable threats to the outlook. Furthermore, a steep decline in global economic activity could weigh on export growth and the domestic economy.

Longer term, the South Korean authorities’ ongoing planning to identify new growth engines could boost future economic potential. The “Korean Green New Deal” aims to increase investment in green and digital sectors (including solar panels and wind turbines, electric vehicles, cloud computing and artificial intelligence) and strengthen the employment safety net. That is balanced against demographic pressures that pose economic and fiscal challenges over the longer term. To counter these challenges, the government announced in late 2023 a new “workcation” visa, which aims to encourage greater movement of human capital and support productivity growth.

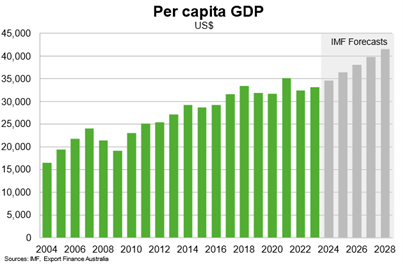

South Korea is one of the few countries that has successfully transformed itself from a low-income to a high-income economy. As the economy continues to grow, the IMF projects GDP per capita to rise toward US$42,000 in 2028 from an estimated US$33,100 in 2023. But income inequality remains high. The government has increased minimum wages on an annual basis, provided basic pensions for the elderly and greater unemployment benefits for the youth to help tackle income inequality. But high inflation, tight monetary policy and high household debt are squeezing household budgets, hitting the vulnerable particularly hard.

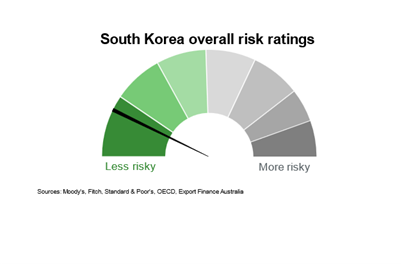

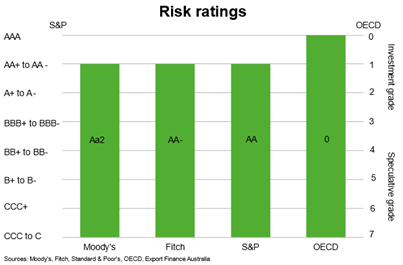

Country risk

Country risk in South Korea is low. This suggests a low likelihood that South Korea will be unable and/or unwilling to meet its external debt obligations. The three private ratings agencies have high investment grade credit ratings for South Korea.

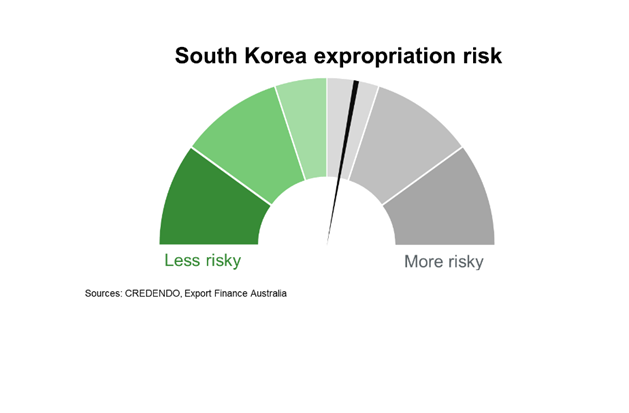

The risk of expropriation is moderate. According to the US investment climate statements, South Korea follows generally accepted principles of international law with respect to expropriation. South Korean law protects foreign-invested enterprise property from expropriation or requisition. Private property can be expropriated for a public purpose—like urban redevelopment, building new industrial complexes, or constructing roads. Property owners are entitled to prompt compensation at fair market value.

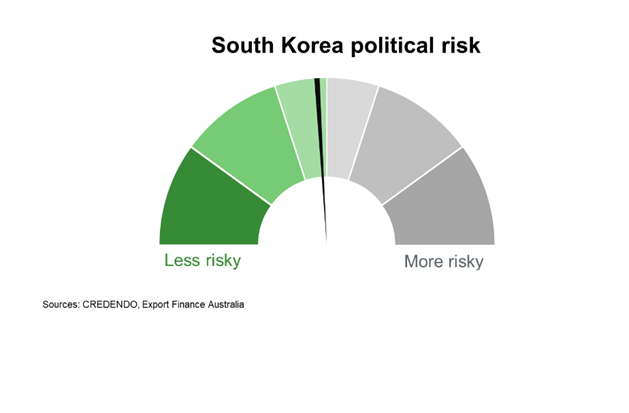

Political risk is also moderate, and is mainly driven by long-standing tensions with North Korea. Periodic tensions in South Korea's bilateral relations with larger neighbours, including China and Japan, have led to occasional disruptions to the economy. The domestic political environment remains relatively stable.

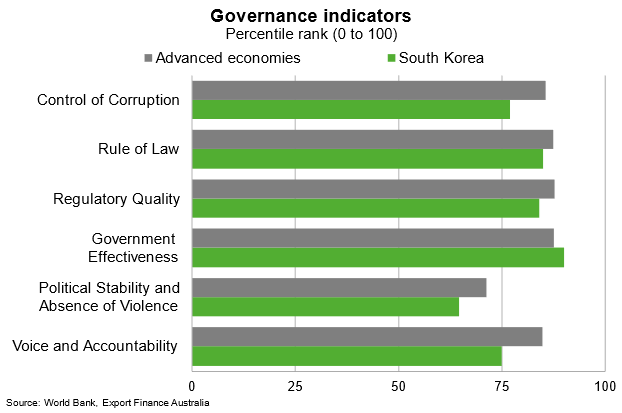

Fiscal, monetary and regulatory institutions are very strong, as reflected in a long-track record of robust economic and fiscal management. But governance indicators are slightly lower than most other advanced economies. Corruption remains a significant constraint on the institutional environment and doing business. This reflects, in part, perceptions of the disproportionate influence of the country's chaebol on the economy and government. Ongoing government efforts to reduce corruption could strengthen governance standards over the medium to long term.

Bilateral relations

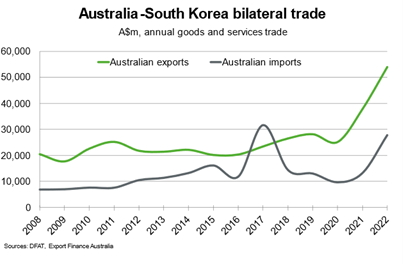

South Korea is Australia’s 4th largest trading partner, after China, Japan and the US. Bilateral trade reached $81.9 billion in 2022, 60% higher than in 2021. The increase in two-way trade in 2022 reflected higher Australian exports of coal, LNG and iron ore as South Korea’s economy recovered from the pandemic and higher commodity prices as a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Australia is also among the world’s biggest suppliers of agricultural and food related products to South Korea. Australia’s main goods imports from South Korea included refined petroleum and passenger motor vehicles in 2022.

The KAFTA—Australia’s bilateral trade agreement with Korea—which came into force in December 2014, lowered tariffs between the two countries and has significantly strengthened trade relations. Other free trade agreements (FTAs) include the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). Bilateral and multilateral FTAs support opportunities for Australian suppliers of legal, accounting and telecommunications services and enhances market access for other services, including financial services and education.

Over the longer term, South Korea’s focus on boosting “green” and “digital” investments is positive for Australian goods exporters, particularly of iron ore, copper, food and beverage. It also opens opportunities for aerospace, automotive, shipbuilding, electronics and machinery exporters to supply South Korea’s strong manufacturing base.

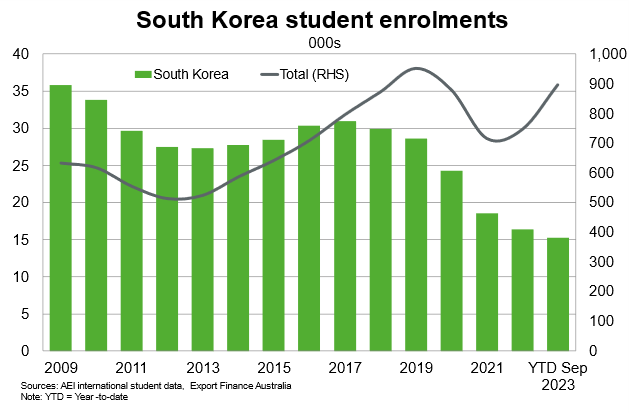

Services trade between the two countries is smaller than goods trade. Total services trade stood at $1.7 billion in 2022, more than 30% lower than its 10-year average. South Korea was Australia’s 13th largest source of international students as of September 2023, down from 6th in 2016. South Korean student enrolments in Australia have been falling since 2018, due to a decline in demand for vocational education training.

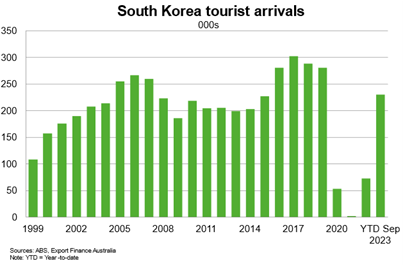

South Korean tourism to Australia has recovered following the reopening of international borders, though visitor arrivals remain below pre-pandemic levels. A competitive Australian dollar and another year of recovery in international travel should support further demand for Australian tourism, and broader services exports, in 2024.

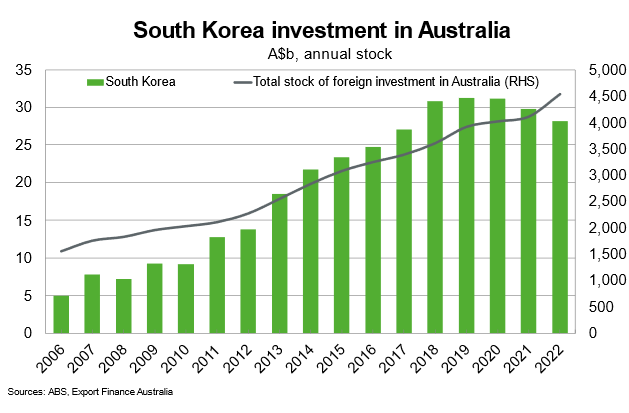

South Korean investment in Australia totalled $28 billion in 2022, slightly softer than in recent years but still sharply higher relative to 15 years earlier. Major South Korean investors in Australia include POSCO, the Korean Gas Company (KOGAS), SK E&S and Korea Zinc. Opportunities exist for investment in critical minerals, as South Korea ramps up its investment in low-emissions technology to achieve its net zero carbon emissions target by 2050.

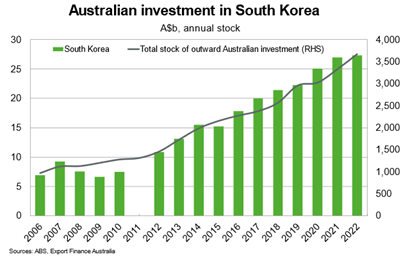

Australian investment in South Korea, at more than $27 billion in 2022, has been growing solidly over several years. A large proportion of Australian investment has been made by financial and infrastructure firms.