Sri Lanka—IMF bailout to ease economic crisis, but risks remain

The IMF approved a four-year, US$3 billion (3.4% of GDP) bailout program for Sri Lanka last month, which aims to restore economic stability and debt sustainability. The approval enabled an immediate disbursement of US$333 million to the government and will catalyse financial support from other development partners. This will help alleviate severe food and fuel shortages which led to violent protests and forced then-President Gotabaya Rajapaksa to resign last July. However, the country faces a long and difficult path to economic recovery.

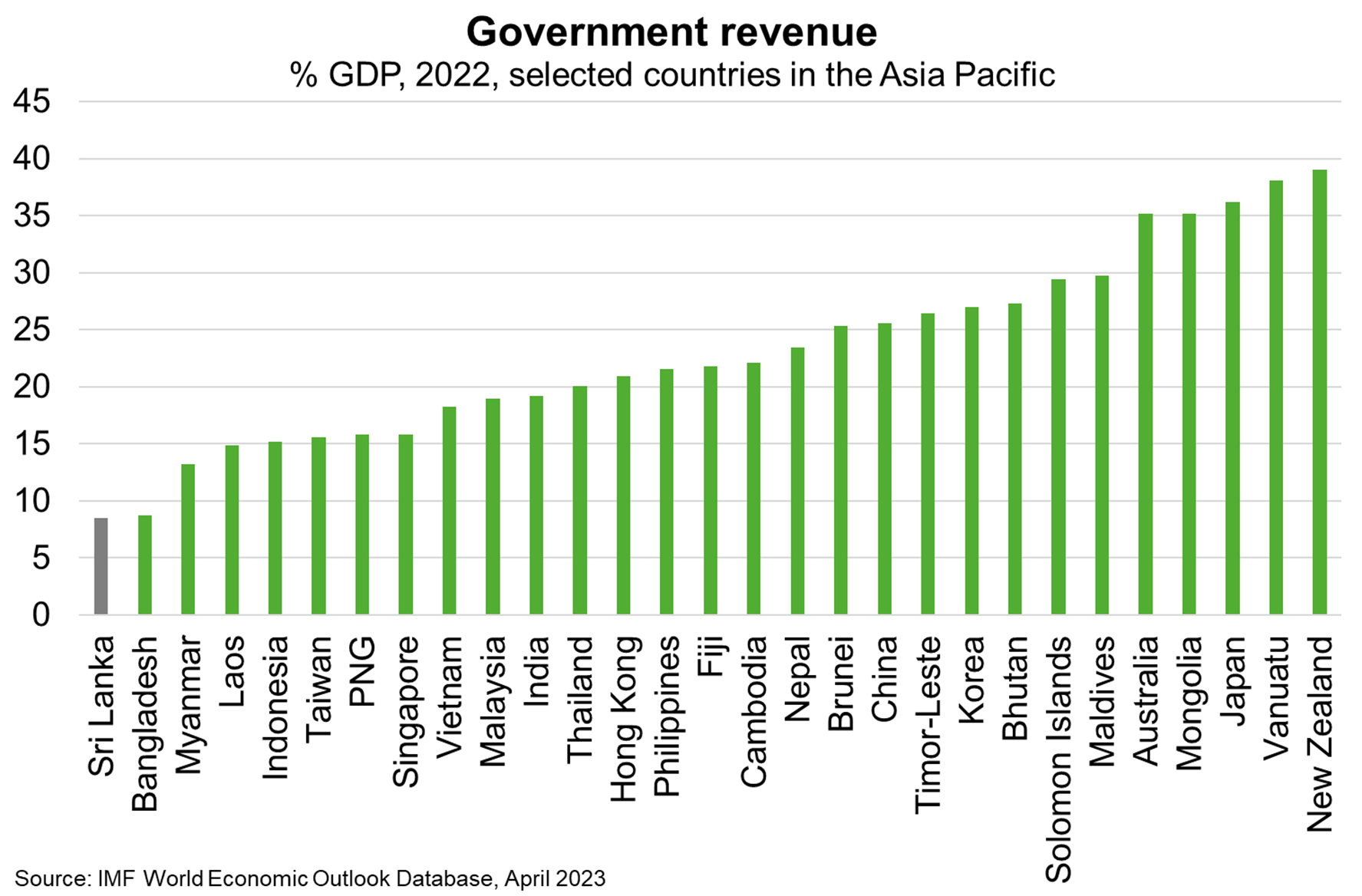

First, the disbursement of subsequent IMF tranches requires implementing further critical (Chart) but ambitious revenue raising measures that may reignite social and political instability amid difficult economic conditions. While the economy is forecast to contract for a second successive year in 2023 (albeit less sharply than the 8.7% contraction in 2022), the central bank was forced to hike interest rates 100 bps to 15.5% last month to contain inflation (50% in March).

Second, subsequent IMF tranches will require advancing debt restructuring negotiations with Sri Lanka’s creditors, including China. More complicated debt restructuring processes are a global challenge. Public debt ratios rose dramatically during the pandemic, increasing the risk of debt distress amid higher global interest rates, weak economic growth prospects and a stronger US dollar. Indeed, over half of all low-income economies are either experiencing, or are at high risk of, debt distress. But China’s emergence as the world’s largest bilateral creditor complicates the well-established restructuring process of ‘Paris Club’ lenders. Beijing is reluctant to write down loans, but the IMF is unable to lend to countries with unsustainable debts. As worrying examples, Suriname and Zambia secured IMF bailouts after defaulting during COIVD-19 but are yet to unlock the bulk of their funds due to lack of progress on debt restructuring.