US—Polarised debt ceiling debate has economic and financial costs

The debt ceiling is a limit imposed by Congress on the amount the US Federal government can borrow. After the current limit of US$31.4 trillion (117% of GDP) was reached in January 2023, US Treasury began using ‘extraordinary measures’ to meet the government’s financial obligations. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen warns that June 5 is a ‘hard deadline’, after which the US will have insufficient cash to pay its bills, unless the White House and lawmakers agree to raise or suspend the ceiling.

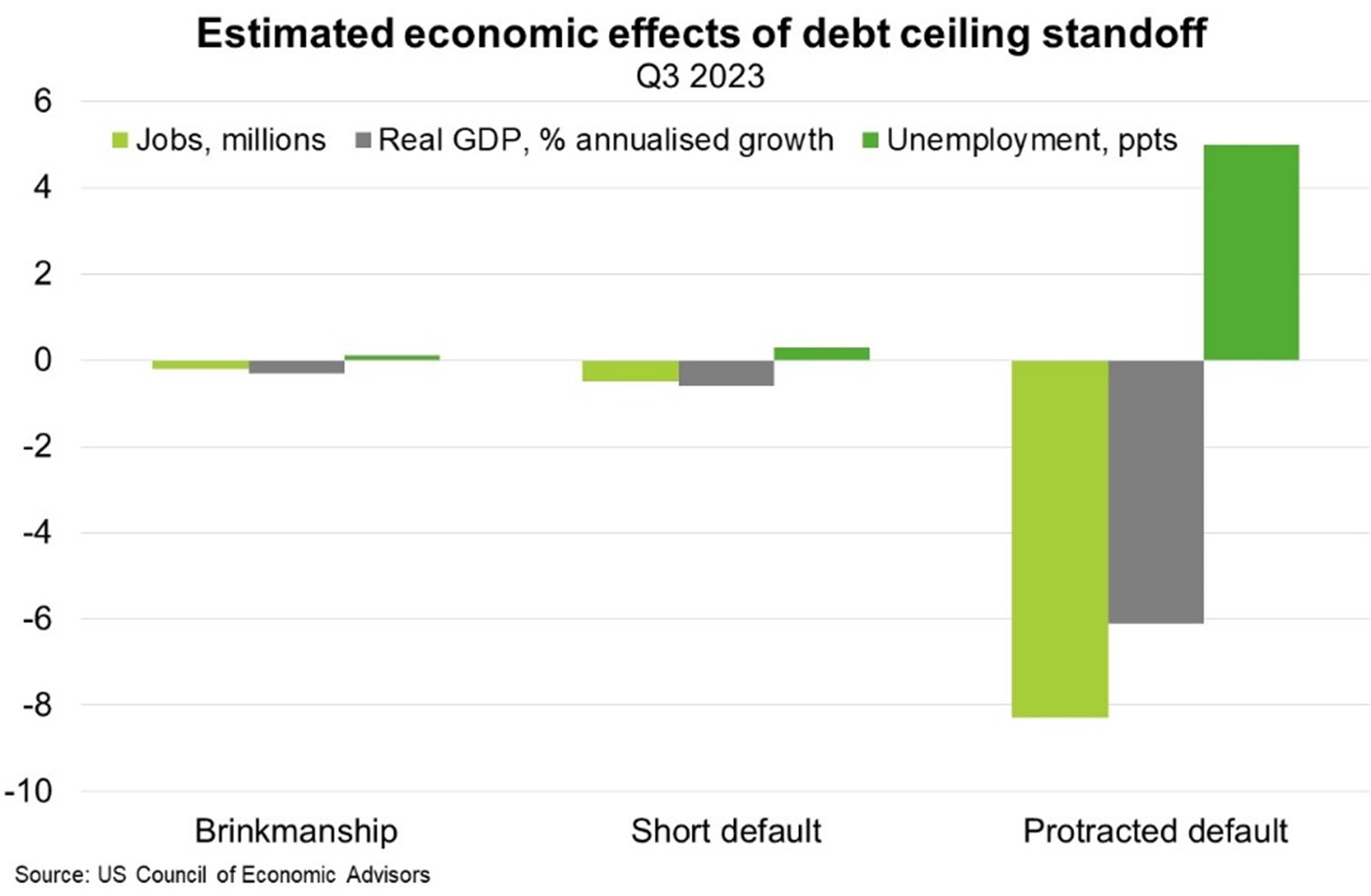

The debt ceiling has precipitated political battles for decades. Congress has raised or temporarily extended the debt limit 78 times since 1960. Another last-minute compromise is the most likely scenario, given the disastrous consequences of an unprecedented US default. The Council of Economic Advisors warns that a short default would reduce annual GDP by 0.6% while a protracted default would entail an immediate, sharp US recession in the order of the GFC. In the first full quarter of a simulated debt ceiling breach, the stock market falls 45% and unemployment increases 5 ppts (Chart).

Even if Congress raises the debt ceiling before such a dire outcome, political brinkmanship exerts an economic toll. First, US borrowing costs increased substantially during May for securities maturing in early June, increasing the government’s fiscal burden. Indeed, the 2011 debt ceiling standoff increased the government’s borrowing costs by an estimated US$1.3 billion. Second, worsening financial market stress indicators and an associated loss of business and household confidence drag on economic performance. Third, such confrontations erode government effectiveness. Indeed, political brinkmanship over the debt ceiling contributed to S&P downgrading the US credit rating in 2011, citing weakened ‘effectiveness, stability and predictability of American policymaking and political institutions’.