Hong Kong—Economic challenges hit demand for Australian exports

Hong Kong’s economy has faced several shocks in the past years, including anti-government protests in 2019, China’s implementation of the National Security Law in 2020 and three years of COVID lockdowns. Against this background, there has been an exodus of people and some foreign businesses moved regional headquarters to other locations like Singapore. This year’s economic recovery in China has helped normalise economic activity, through increasing tourism and retail trade. But high inflation, tighter financing conditions and weaker global demand are slowing growth momentum. The IMF forecasts growth to fall to 2.9% in 2024 from 4.3% in 2023.

Increasing economic, financial and political ties to China offers benefits to Hong Kong. China is Hong Kong’s largest export market and the second largest source of inward direct investment. The rise in mainland Chinese firms operating in Hong Kong is boosting demand for local services. But the close relationship also adds to economic challenges. Reliance on mainland demand leaves Hong Kong vulnerable to a period of lower Chinese growth. Hong Kong’s perceived autonomy over economic management, rule of law and freedom of speech is also diminishing. Indeed, Singapore recently overtook Hong Kong to become the world’s freest economy. Ongoing US-China geopolitical tensions—that could result in more US sanctions against China—is an additional risk to Hong Kong’s economy.

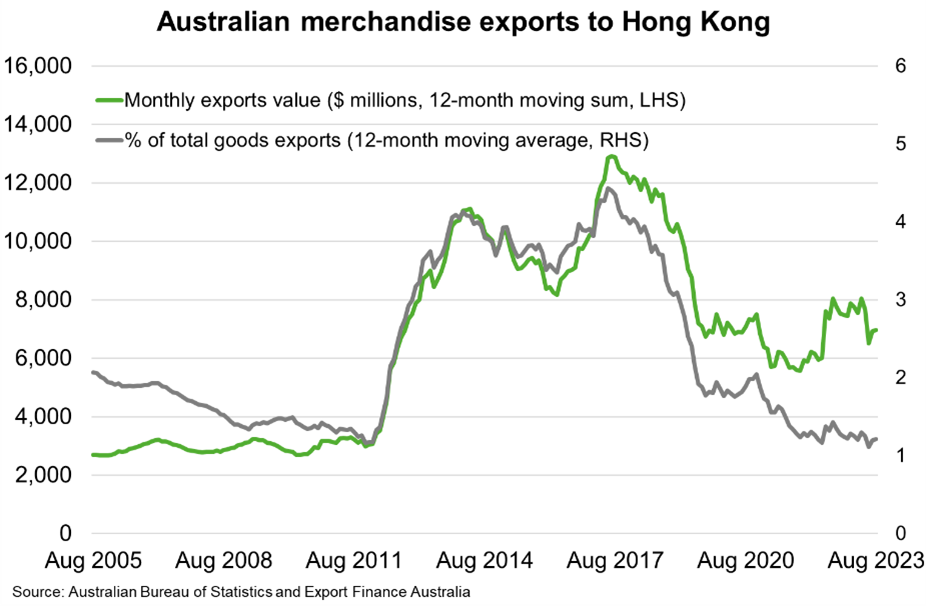

Hong Kong’s economic challenges have contributed to lower demand for Australian exports. Goods exports to Hong Kong remain well below peak levels in 2017 and have yet to meaningfully surpass pre-pandemic levels (Chart). The prospect of slower growth in Hong Kong—Australia’s 12th largest export market in 2022—is a hurdle for Australian exports, particularly food (including dairy, meat and seafood) and beverages (including wine) that supply Hong Kong’s retail and hospitality sectors.