© Export Finance Australia

The views expressed in World Risk Developments represent those of Export Finance Australia at the time of publication and are subject to change. They do not represent the views of the Australian Government. The information in this report is published for general information only and does not comprise advice or a recommendation of any kind. While Export Finance Australia endeavours to ensure this information is accurate and current at the time of publication, Export Finance Australia makes no representation or warranty as to its reliability, accuracy or completeness. To the maximum extent permitted by law, Export Finance Australia will not be liable to you or any other person for any loss or damage suffered or incurred by any person arising from any act, or failure to act, on the basis of any information or opinions contained in this report.

Bangladesh—Political instability exacerbates economic risks

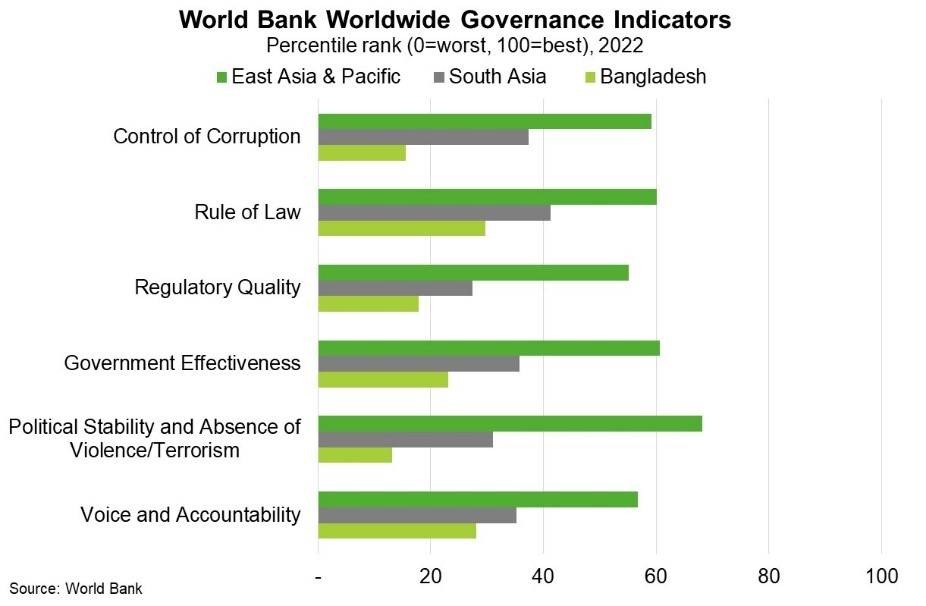

Sheikh Hasina—who led Bangladesh for 20 of the past 28 years—resigned as prime minister and fled Bangladesh this month following violent demonstrations. What began as student-led protests opposing public-sector job quotas quickly escalated into an anti-government movement. Despite robust GDP growth, unrest was driven by rising living costs, stagnant labour markets, violent crackdowns on dissent and corruption (Chart). Economist Muhammad Yunus—a Nobel laureate and microfinance pioneer—will lead an interim administration. Yunus is well credentialled to stabilise the economy, secure ongoing support from development partners, and restore business confidence. The interim administration’s composition will also satisfy student protestors.

However, amid a highly polarised society, challenges to restoring constitutional order are significant. Bangladesh has long been characterised by dynastic power politics and cronyism. A functional electoral democracy will require a) judicial and other institutions to be substantially strengthened, and b) new political leaders to fill the vacuum left by Hasina’s unexpected departure.

The political crisis also worsens economic and public finance risks. Bangladesh began a 42-month, US$4.7 billion IMF program in January 2023 to preserve macroeconomic stability. However, high commodity prices and global financial tightening continue to pressure foreign reserves and the taka. Fitch and S&P recently downgraded Bangladesh’s credit rating, the latter noting that the political situation “has exacerbated the banking industry’s frailties, including weak liquidity, thin capital buffers, and ailing asset quality”. Credit buffers may deteriorate further if lower remittances and factory closures are prolonged. Exports of garments were US$50 billion last financial year (90% of exports and 11% of GDP). Buttressing economic stability requires implementing long overdue economic reforms and improving governance. That said, a large pool of low-cost labour suggests Bangladesh—Australia’s 25th largest export market—would be hard to replace in the long term.