© Export Finance Australia

The views expressed in World Risk Developments represent those of Export Finance Australia at the time of publication and are subject to change. They do not represent the views of the Australian Government. The information in this report is published for general information only and does not comprise advice or a recommendation of any kind. While Export Finance Australia endeavours to ensure this information is accurate and current at the time of publication, Export Finance Australia makes no representation or warranty as to its reliability, accuracy or completeness. To the maximum extent permitted by law, Export Finance Australia will not be liable to you or any other person for any loss or damage suffered or incurred by any person arising from any act, or failure to act, on the basis of any information or opinions contained in this report.

World—Falling productivity growth drags on economic prospects

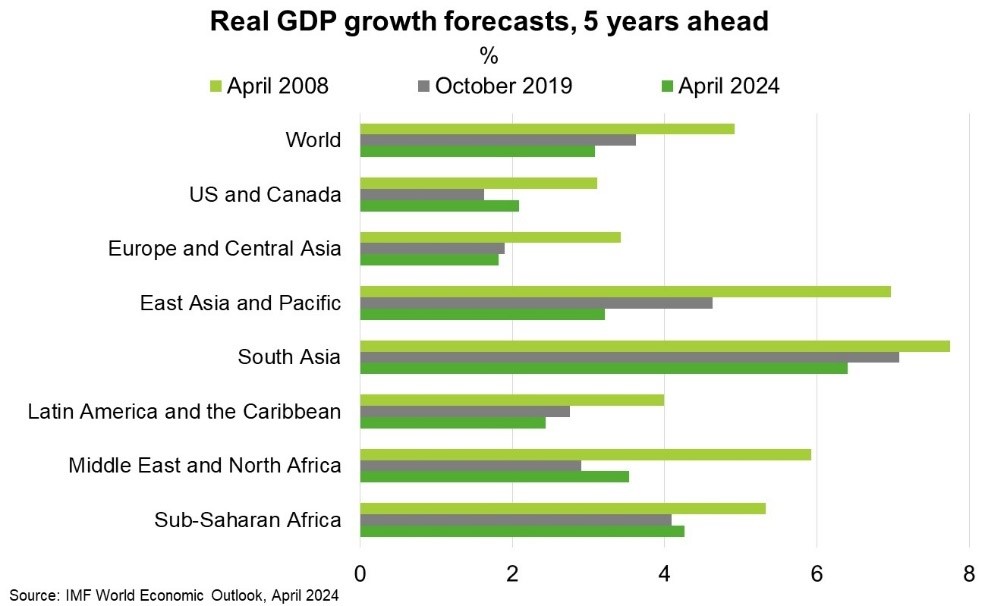

The global economy has demonstrated remarkable resilience to recent shocks. However, medium term prospects for growth in world output and trade remain the lowest in decades. Expectations for medium term growth have been revised down across all income groups and regions, most significantly in emerging markets (Chart). Dimmer growth prospects in China and other large emerging markets—that account for an increasing share of the global economy and Australian exports—will transmit through highly integrated supply chains. IMF research suggests that global growth could stagnate at just 2.8% by the end of the decade, without policy interventions or technology breakthroughs. That’s a drop of 1 ppt from pre-COVID levels.

Over half of the decline in global growth owes to a marked deceleration in productivity growth—the ratio of output to resources consumed. In advanced economies, annual productivity growth fell from 1.4% during 1995–2000 to 0.4% after the pandemic. Emerging markets productivity fell from 2.5% during 2001–07 to 0.8%. The slowdown reflects a retreat in labour force participation amid population ageing, weaker business investment, and—most importantly—persistent structural frictions that prevent resources from being allocated to more productive firms, including regulatory barriers, rigid labour markets, financing constraints and lack of trade openness. Ongoing geoeconomic fragmentation will limit cross-border flows of goods, services, capital and workers, thereby reducing the scope for efficiency gains from specialisation and competition.

Former Italian Prime Minister and European Central Bank President Mario Draghi’s recent European Competitiveness report warns that stagnant GDP growth could lead to unsustainable public debt. This reflects historically high public debt-to-GDP ratios, potentially higher real interest rates and rising spending needs for decarbonisation, digitalisation and defence. Expectations of weaker growth could also deter investment in capital and technology, and so, may become self-fulfilling.