Emerging markets—High food prices raise social risks

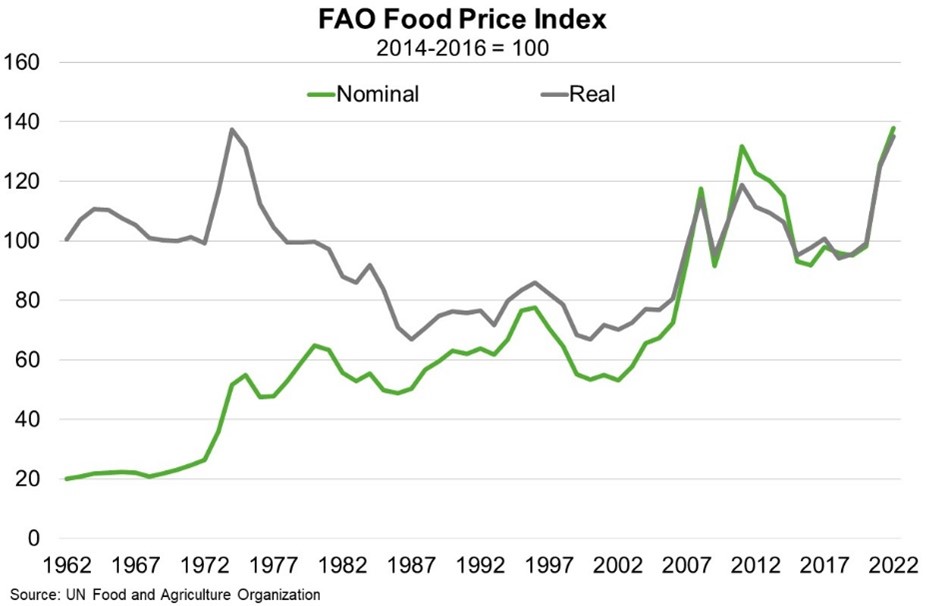

Global food prices are at their highest level since 1974 (Chart), reflecting adverse weather conditions, higher input costs, pandemic-related supply chain and shipping disruptions, and stockpiling and export restrictions in some countries. The Russia-Ukraine crisis will worsen supply challenges. Ukraine and Russia are major exporters of agricultural commodities essential for food security; accounting for 26% of wheat, 15% of corn and 64% of sunflower seed oil exports globally. Russia and Belarus are also large fertiliser producers. The military conflict and associated sanctions will induce physical and financial supply disruptions and increase energy and fertiliser input costs.

Higher food prices will disproportionately hurt emerging markets, where relatively low per capita incomes mean food staples account for a larger share of household spending. Fiscal pressures will also increase in countries with food subsidies. The Middle East and Africa appear most exposed. Rapid population growth combined with water scarcity and vulnerability to severe weather leaves these regions particularly import dependent. For example, Egypt is the world’s largest wheat importer, with Russia and Ukraine supplying 86% of its needs. The cost of Egypt’s food subsidies—which have maintained the price of 20 loaves of pita at one Egyptian pound since 1989—will rise dramatically. Price rises for basic commodities and food are already being felt, with the Central Bank of Egypt raising interest rates in response to a 17% depreciation of the Egyptian pound. Aside from its health and economic impacts, food insecurity also has the potential to fuel socio‑political instability. The World Bank’s Food Price Crisis Observatory identifies food riot events in 38 countries from 2007 to 2014. Indeed, Egypt’s bread subsidy was abolished in 1977 only to be reinstituted within days after riots were quelled by the army.

Australia is a significant exporter of wheat (6th largest globally) and barley (2nd largest globally). While forward contracts will limit the short-term upside, higher prices and demand for Australian wheat may benefit Australian growers in the medium term and offset some of the impacts of higher fuel and fertiliser prices.