United Kingdom—High energy prices drive stagflation

The Bank of England (BoE) forecast consumer price inflation to rise to a 40-year high of around 10% this year. Much of the price pressure is driven by forces beyond the BoE’s control—such as shocks to commodity markets and supply chain disruptions from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and COVID-19 developments in China. Still, the BoE raised interest rates by 25 basis points to 1% this month, the fourth consecutive increase, to help contain inflation expectations and anchor domestic drivers of inflation, like wages and rents.

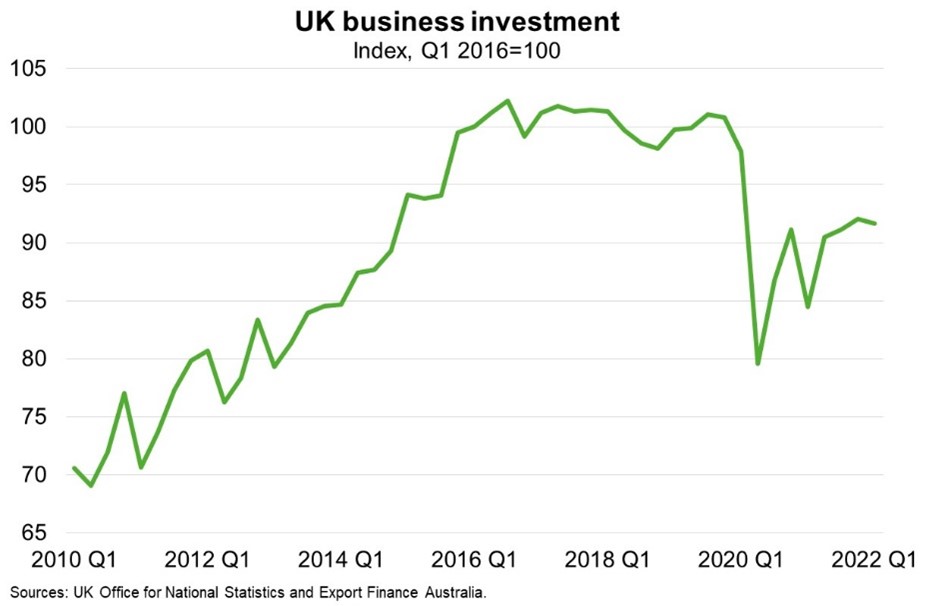

Higher interest rates come despite a weak economic outlook; the BoE expects GDP to contract in Q4 2022 and remain broadly flat in 2023, while unemployment rises to 5.5% in three years’ time (from 3.8% in February). Similarly, the National Institute of Economic and Social Research predicts GDP will fall in the third and fourth quarters of 2022—meaning recession. Reflecting heightened economic uncertainty, business investment fell by 0.5% in Q1 and is now 9.1% below pre-pandemic levels and 8.4% below pre-Brexit referendum levels (Chart). Meanwhile, consumer confidence is at its second lowest level since records began in 1974, limiting the potential for savings accumulated during the pandemic to buoy consumer spending. The trade deficit also widened to a record share of GDP in Q1, with imports up 9.3%, largely reflecting higher energy prices, and exports down 4.9%.

The UK outlook suggests the worst combination of high inflation and stagnant economic demand—or ‘stagflation’—since the 1970s. In contrast to that period, the world is now less reliant on oil, central banks are more credible, and automatic wage-setting mechanisms are less prevalent. While these factors will curtail upward price pressures, there will nonetheless be significant strain on consumers and businesses in Australia’s fifth largest export market.